A lot of people are worrying about AI art: human artists concerned for their livelihood, the loss of artistic meaning, and the tedium of hedonic adaptation that may set in when AI makes beauty too cheap to meter. Those are all real, legitimate concerns. However, I want to zoom out, and think more broadly about what we care about in art, and why.

It turns out there’s a conflict between caring about beauty, elegance, craft, and aesthetic value on the one hand, and genuineness, authenticity, and relic value on the other. Sometimes we think the former matters more than the latter, sometimes the reverse. I have a bunch of examples to think about first and then I’ll mull over what the implications are for AI art.

Fakes are bad

Henricus (‘Han’) van Meegeren was one of the most successful forgers of the 20th century, creating numerous paintings in the style of the 17th-century Dutch masters such as Frans Hals, Pieter de Hooch, Gerard ter Borch, and especially Johannes Vermeer. Van Meegeren’s masterpiece, Supper at Emmaus, was executed with such craftsmanship and detail that it fooled all the leading experts of the day to conclude that it was a genuine Vermeer. Van Meegeren was also famous for duping Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring into buying another fake Vermeer, Christ and the Adulteress. He made major bank on these hoaxes and bought a bunch of mansions and filled them with genuine Old Masters art.

After World War II, Dutch authorities charged van Meegeren with selling cultural treasures to the Nazis and, to escape the accusation, he had to finally confess that he was a forger. The Dutch promptly charged him with that instead.

During van Meegeren’s trial he was reported as saying, “Yesterday this picture was worth millions. Experts and arts lovers came from all over the world to see it. Today it is worth nothing and nobody would cross the road even to see it for free. But the picture has not changed. What’s different?” The thing is, Van Meegeren is right: the aesthetic value of the painting had not changed. It was still as creatively composed, elegantly painted, and pleasing to the eye as it was before. What is different is that its perceived authenticity, its value as a relic, plummeted to nothing.

The example of Van Meegeren puts the lie to the naïve view that art is appreciated solely for its beauty.

I can’t help but note that as soon as Van Meegeren’s work was exposed as forgeries, immediately there was historical revisionism: his work was obviously mediocre, clearly inferior to Vermeer, “heavy-handed and awkward,” blah, blah, blah. It’s amazing how things are obvious after the fact.

Fakes are good

The privileging of relic value over aesthetic value just described is not universal. Byung-Chul Han argues that there is a longstanding and respected tradition in China of shanzhai, or fakes. In the West, forgers like van Meegeren are arrested, but in China, a good forger is revered. Han writes, “Chang Dai-chien, one of the best-known Chinese painters of the twentieth century, got his breakthrough when a famous collector exchanged an original Old Master for his forgery.” The breakthrough was not because Dai-chien had perpetrated a legendary scam or exhibited some Robin Hood-like civil disobedience. Rather, it was because he had proven that his work was every bit as good as the Old Masters—in fact, it was better. Therefore his canvas itself was better.

Shanzhai is a Platonic view: a painting like Hiroshige’s Plum Garden in Kameido is but a flawed physical example of the unobtainable Platonic form of the perfect Plum Garden in Kameido. An expert forger could produce a superior version of Plum Garden in Kameido to Hiroshige’s, one that is even closer to the Platonic form. A true connoisseur would prefer the newer painting, the one with greater aesthetic value. Producing such a painting was Dai-chien’s achievement.

The shanzhai tradition might seem weird and alien. In How Pleasure Works, Paul Bloom writes, “If I owned a painting by Chagall, I would not be pleased if someone switched it with a duplicate, even if I couldn’t tell the difference. I want that painting, not merely something that looks just like it” (p. 87). Bloom’s attitude is a typical one in the Western art world. But 10,000 miles away, a Chinese collector of paintings cares only for the beauty of the work, and not whose name is signed or what year it was made. A superior forgery is superior tout court.

If the Chinese view sounds strange—that relic value means little or nothing and aesthetic value is all—consider fake luxury goods, like handbags and watches. There are way more “Louis Vuitton” and “Coach” bags out there than there are Louis Vuitton and Coach bags.

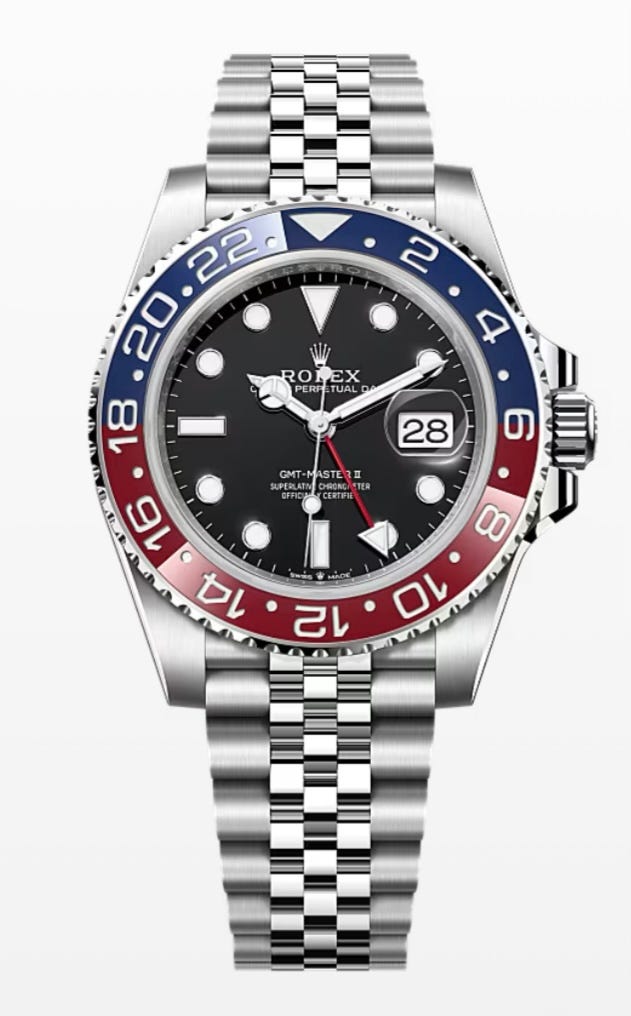

You can also buy fakes of any famous watch brand, not cheap, easily spotted knockoffs but carefully crafted copies costing hundreds of dollars. Even grand complications have been replicated. These watches, largely made in China, are so sophisticated that only trained experts using jeweller’s loupes are able to tell the difference between them and Swiss originals.

Do you think you can tell the difference between these two watches? Here’s a phony Rolex GMT-Master II and here’s a real one. The fake is $650, the genuine is $11,300. What aesthetic reason is there to prefer the real one? I’m not asking why you would want a thing worth more money over a thing worth less. If somebody were to give me a Rolex, I’d want the real one—I could go sell it and buy books. But unless you have money to burn, why would you buy the genuine? The answer can’t be because the fine finishing of a part deep inside the automatic winder is microscopically smoother. The same stainless steel, sapphire crystal, ceramic face, and bracelet mechanism is used in both; to the naked eye, they look identical.

If it sounds ridiculous to spend thousands of dollars on something no more beautiful, reliable, or impressive, it is because aesthetic value seems much more important than relic value. Quite the opposite result from Van Meegeren!

Fakes are best

Sometimes copies actually improve on the originals. I think the best example here is musical covers. Some musical covers are transformative, like Jeff Buckley’s cover of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah’, but aficionados still know that it is Cohen’s original song. However, there are many covers so iconic that very, very few people could name the original artist. Here are some examples with the most famous performer in parentheses. See how many original artists you can name.

‘Hey Joe’ (Jimi Hendrix)

‘Respect’ (Aretha Franklin)

‘Blinded by the Light’ (Manfred Mann)

‘You Really Got Me’ (Van Halen)

‘Dazed and Confused’ (Led Zeppelin)

‘Cocaine’ (Eric Clapton)

‘Black Magic Woman’ (Santana)

‘John Barleycorn Must Die’ (Traffic)

‘When the Levee Breaks’ (Led Zeppelin)

‘House of the Rising Sun’ (The Animals)

‘Tainted Love’ (Soft Cell)

‘Twist and Shout’ (The Beatles)

No one thinks that these artists are frauds, or that they are in some way culpably dishonest. It is more plausible to view their contributions Platonically: Hendrix’s brilliant interpretation of ‘Hey Joe’ more closely approaches the aesthetic ideal of that song than the long-forgotten and much inferior (but first) recording by The Leaves. If the Dutch treated paintings the same way as songs, van Meegeren would not have gone to prison; indeed museums might seek his works more than Vermeer.

Another example of copies improving on the original is bespoke replica cars. Some classic cars are extremely rare and insanely expensive, e.g. the Porsche 550 Spyder (the car actor James Dean was driving when he died), the Ferrari 1963 California Spyder (the hero car in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off), and the Shelby AC Cobra.

How could a modern replica be better than the original? Disc brakes instead of drum brakes, a fuel-injected engine, high-spec CAD-CAM parts and metallurgy, contemporary paint and finishing technology, GPS speedometer and odometer, seatbelts, and modern tires, that’s how. A high quality replica will be more reliable, durable, safe, and practical than an original antique. You may be better off investing in an $18 million Ferrari, but you’re better off driving a $100,000 reproduction. A 1:1 replica will be just as beautiful and way more practical than the original.

AI art

How does of any of this help us understand AI art? Well, a common criticism of AI art is that it is just copying, that it’s a simulacrum, pastiche, or plagiarism of human art, that it is phony. At least half of the AI art takes on Substack are some version of this. Those critics are missing the target. Let’s apply the lesson from what I wrote above: fakes can be good, and in some instances the best! So just reflexively complaining that AI art is fake is really beside the point.

More useful is to apply the framework of relic vs. aesthetic value.

A key fact about AI art is that it has no relic value; there’s no such thing as “the original” of a piece of AI art. Relics don’t have to be unique or even old: restricted runs give things relic value, like numbered and signed giclée prints, or limited editions of books. So what relic value could possibly attach to Stained-Glass Supper at Emmaus (which I asked ChatGPT to create)?

The only answer I can come up with is if there were a non-fungible token (NFT) for the piece. NFTs are a unique digital ledger of ownership for a digital object. While we could make a million identical copies of Stained-Glass Supper at Emmaus, with no one of them any better than the next, you can’t do that with an NFT. The whole point of an NFT is to imbue one copy with relic value, even though it does not enhance the object in any other way.

That was the theory, anyway. NFTs are apparently dead in the water. In the end nobody was really convinced that they were more than a gimmick or that they added anything of value to digital objects.

The loss of possible relic value is a blow to AI art. Often background knowledge and contextual understanding are needed for the full aesthetic experience of a thing. The awe one feels in encountering the Antikythera Mechanism in Athens’s National Archaeological Museum was surely not felt by the sailors in 1901 who hauled up a bizarre, unknown lump of bronze from an ancient shipwreck. To take another example, a blot of mud on its own has little aesthetic value, but as painter Eugene Delacroix famously said, “Give me mud, let me surround it as I think fit, and it shall be the radiant flesh of Venus.” In this case, context is all.

By hoovering up all human art in its training data, AIs have flattened context. The history of art is seen only from the God’s eye perspective and not as a practice in our cultural moment. Without creating a piece of art that matters as an object, AI is not going to be creating things that have religious or social significance or a unique niche in history. I don’t doubt that it can create beautiful or striking art. The question for us is whether, like watches and musical covers, that’s all that matters.

I’m wondering if this Chinese attitude toward fakes partly explains their approach to intellectual property?

Oh yeah, musical covers are a very good example. I thought of Metallica's famous cover albums that both helped Metallica artists to overcome burnout from sudden fame and boosted popularity of the songs they took, especially since they took extra steps to seek out lesser known artists, not just take something from a different genre, reimagine it as hard rock/heavy metal and capitalise on the popularity of the original