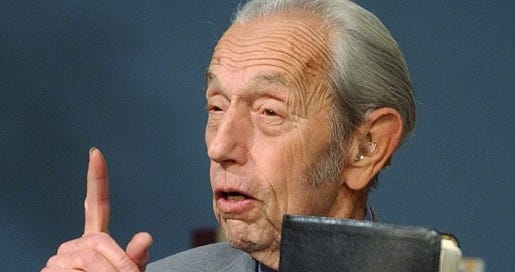

Remember when the world ended on May 21, 2011? Yeah, me neither. But thousands of people thought that it would, because they believed Harold Camping, an elderly radio preacher with a deep monotone voice who was obsessed with predicting the end of the world. His first doomsday prediction was September 6, 1994, which turned out to be one of the most boring days in history. Camping’s response was “whoopsie! How about September 29?” When that also turned out to be a nothingburger, Camping proposed October 2. Apparently the most exciting thing to happen that day was someone won a football game.

Then Camping waited a few more years, presumably furiously working on his calculations, and delivered his best-known prediction: May 21, 2011. After exactly nothing happened once again on that date, Camping re-did the math once more, this time declaring that God had in fact delivered a “spiritual judgment” on May 21, but the actual fire and brimstone stuff would arrive on October 24. Camping’s own world ended not too long after that and so did his doomsday ministry. That’s not always the case for doomsayers, though—the 7th Day Adventists are still going strong with over 22 million members, nearly two centuries after their founder promoted a series of failed dates for the Rapture.

People believe weird things. The Earth is flat, lizardmen secretly run the government, ghosts are real, Bigfoot lives behind their house, Qanon has a pipeline to the secret truth, judgment day is next week, whatever. There are three puzzles here:

1. Why does anyone start believing these things at all?

2. Why do they keep believing them no matter what new evidence is discovered?

3. Is it always a mistake?

Right now, I want to think about (2) and (3). After botching his end-of-the-world forecasts several times, Camping gained more followers. Talk to some true believers in flat Earth, or someone who thinks the 2020 US presidential election was a fraud. It won’t take long before you get the sense that there is no possible evidence that will shake their conviction. This is mysterious. You’d think that if we were all devoted to discovering the truth that we would automatically update our beliefs in the light of new information. Like “this guy Camping sucks at predicting the end of the world. I’m going to reduce my confidence in him.” But that’s clearly not what’s going on. There’s not a downgrading of some beliefs and a strengthening of others; some beliefs are evidently untouchable by reason. So are these dogmatists just stupid or what?

No, I don’t think so. Sometimes it is perfectly reasonable to stake out a foundational axiom and dismiss anything in conflict with it. For example, a quick scientific test for a proposed hypothesis is whether the hypothesis would permit perpetual motion. If the answer is yes, the hypothesis is chucked without further ado; perpetual motion violates the first law of thermodynamics. If an inventor shows up with an apparent perpetual motion machine, the task is to show where it is secretly drawing energy so there is in fact a net loss.

The general problem is how to distinguish between those claims we should hang on to regardless of apparent counterevidence, and those we should revise or discard. To look at this problem I’m going to reach deep into the JSTOR archive.

Three-quarters of a century ago, the Harvard philosopher/logician Willard Van Orman Quine published a scholarly paper entitled “Two Dogmas of Empiricism” in the august journal Philosophical Review. In it he explained how people can defend any kind of wacky thing in order to hang onto their cherished belief that Bigfoot is real, or the Earth is flat, or the government is covering up space aliens, or the end of the world is nigh. Well, Quine didn’t quite realize that his ideas explained those things, but surprisingly, they do.

Here's the backstory. At the time, philosophers were worried that some of the ideas their compatriots were coming up with were literal nonsense. In Martin Heidegger’s lecture What is Metaphysics?, he famously claimed that “the nothing itself noths.” Is that true? False? What’s going on? Nonsense or gibberish can’t be true or false; only sentences that are meaningful can be. That motivated people to find a criterion of meaningfulness. A popular view when Quine wrote was that sentences are meaningful if and only if they can in principle be verified by empirical experience. The verifiability idea came in for a lot of criticisms: what about mathematics? That’s not empirical, so is it nonsense? What about the verifiability principle itself? That can’t be verified empirically, so is it self-refuting? Quine had a very different criticism: he argued that individual sentences on their own cannot be confirmed or disconfirmed by experience. Consider this sentence:

Dolphins are fish.

Is that sentence true? Well, say the verifiability fans, let’s just go out into the world and see. We have the concepts of dolphins and fish, and all we need to do is check and see if the former fits the latter. Hold on though, concepts aren’t handed down by God. We make them up, we develop them for use in our theories of the world. Before we can determine whether something is a fish, we must first come up with taxonomic theory, with its division of living things into kingdoms, phyla, class, order, family, genus, and species. We also have to decide the boundary conditions for dolphins, and how they are distinguished from their closest relatives. Maybe we need to develop phylogenic trees. In short, we have to do a lot of theorizing before we’re in any kind of a position to ask whether dolphins are fish, even if we agree this is an empirical question.

This is why Quine argues that we can’t run out and verify (or disconfirm that) “dolphins are fish” or any other sentence. Even something simple as that one is embedded in a larger theoretical model of the world, one with component parts that are far from self-evident. Quine writes that “our statements about the external world face the tribunal of sense experience not individually but only as a corporate body.” We test our entire theories against the world, and if we have recalcitrant evidence or anomalous results, well, there’s any number of adjustments we might make in the theory to accommodate them.

Quine’s second, related, complaint in “Two Dogmas” is against the view that some propositions are true by definition, or in virtue of the concepts they express, and some are not. For example, with “squares are four-sided plane figures” or “nothing red lacks a color,” or “brothers are male siblings” you don’t need to go do a study, or a poll, or conduct lab-bench science to confirm that they are true. In fact it would be absurd to try. Once you grasp the concepts involved, e.g. you know what a “brother” is, and what “male sibling” means, then you can just see immediately that “brothers are male siblings” must be true and there is no possible experience that could refute it. Denying that brothers are male siblings is likely to be met with puzzlement, if not outright incredulity. You would probably think that the denier didn’t understand the terms involved, or is not a native speaker of English, or was making some kind of a joke. Sentences like these are analytic. Sentences that are not analytic, the ones for which we need empirical evidence, are synthetic.

What’s wrong with the analytic/synthetic distinction? Analytic statements are supposed to be those that stay true no matter what new empirical evidence comes down the road. Nothing can shake them; they are foundational axioms. Quine’s idea is that we could treat any statements as analytic or axiomatic. All we need to do is make radical enough adjustments elsewhere in our theory of the world and our views can be consistent again.

Here’s an example in action. Young-Earth creationists believe that the Earth is about 6000 years old. When confronted with the evidence of dinosaur bones that are hundreds of millions years old, do they abandon the young-Earth theory? Of course not. Instead, they dismiss the dinosaur evidence by claiming that Satan planted bones he made to appear hundreds of millions of years old in order to deceive the unfaithful and lead them through error to eternity in his flames. If we’re going to die on the hill of a 6000-year-old Earth, our task is to interpret everything else to fit that unshakeable fact. Thus the dinosaurs are fraudulent and the Earth is still young.

Here's another example: Monty Python’s famous dead parrot sketch. A dissatisfied customer (John Cleese) returns to a pet shop with a dead parrot, but the pet shop clerk (Michael Palin) insists that the parrot is not dead at all. The clerk tries any number of explanations for the why the parrot only seems dead—it’s resting, it actually did move, it’s stunned, it’s pining for the fjords, if it hadn’t been nailed to its perch it would have muscled through the bars, etc. The clerk is ready to believe anything in order to make “the parrot is alive” come out true.

Hopefully it is clear how Quine’s ideas help explain stubborn beliefs in weird conspiracies and bizarre hypotheses. Sometimes people accuse the true believers in election fraud, flat Earth, or Bigfoot as being uninterested in the evidence. That is completely wrong. These folks are often very interested in the evidence, and write books about the search for Bigfoot, or make lengthy videos giving their reasons for believing in election fraud. The point of contention isn’t really over evidence, but over entire worldviews.

From the outside perspective, all of their purported “evidence” is counterfeit, ambiguous, misleading, or incorporates fallacious reasoning. From the inside perspective of the true believers, it is all other data that must be made to fit with the fundamental fact that Bigfoot is real or the Earth is flat. Election deniers will never be convinced because they have set up their denial as an analytic truth; it will hold come what may. If your inviolable belief is that unrestricted gun ownership is always good, then accusing the Sandy Hook school shooting victims of being “crisis actors” is not far behind.

Quine’s ideas also help explain the persistence of cult leaders. To people not in the cult, it is mystifying why the cult followers never see through the leader’s crazy claims and they defend the most outrageous things. The Quinean answer is that within the cult the leader’s utterances are taken as axiomatic, and everything else must be interpreted in light of that foundational truth. The critics are all liars and cheats who fail to grasp the brilliance of dear leader. Conspiracy theories offer a superficially complete and unified picture of how things work, which is why they are so hard to defeat.

Quine writes that we should choose the “conceptual scheme [best at] predicting future experience in light of past experience.” The posits of science too are merely provisional, and might themselves get replaced in the future. Nothing is sacred. Even mathematics and formal logic are in principle open to revision. For Quine, all the puzzle pieces are on the table at once, and we have to decide which ones don’t fit the picture we are making. There are no easy solutions to conspiracy thinking here, but understanding that at root are deep philosophical issues about theory choice is a step in the right direction.

That doesn’t mean that anything goes, or every conceptual scheme is as good as any other. The ultimate arbiter is the empirical world; we must see how well competing theories explain our experiences and predict future ones. Everyone wants to be a gnostic, to look behind the curtain and gain the secret knowledge of reality, of how things really operate. But in fact we must all be prepared to do the hard work of testing our entire models against our collective experiences, and be willing to abandon even our most cherished assumptions if things do not work out as anticipated. We might have to concede that the parrot is really dead. This is the ultimate task of intellectual honesty, but what’s difficult is seeing this task as liberating instead of frightening.

Really enjoying these essays. Keep it up.