About a year ago I learned to make a good omelette. I’m a pretty decent home cook, but every time I tried to make an omelette it turned out to be a disaster—the interior was undercooked, or it stuck to the pan, or it just looked like a dog’s breakfast. I was not happy about this, because I like omelettes, and wanted to figure out the secret. Before going further, here’s what I want to ask: do you think making omelettes looks easy or looks hard? If you already know how to make excellent omelettes, try to think back to the time before you learned. Did it seem like a challenging task? That’s what I want to think about here, the disconnect between how hard something looks with how hard it actually is. I think we are kind of terrible at calibrating apparent difficulty with genuine difficulty, and that fact explains the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Before plunging in, let me eggsplain how I solved the great omelette mystery. Eventually I got the bright idea of turning to that great repository of practical wisdom, YouTube. Straightaway I started making perfect omelettes. Method: melt a tablespoon of butter over medium heat in a small nonstick pan. Whisk two eggs with a little salt and pepper, and pour into the pan. Start a timer; I use the stopwatch on my phone. On one half of the eggy pan, put fillings like tomatoes, mushrooms, herbs, chopped bacon, whatever. Leave uncovered and cook at medium heat for exactly 2.5 minutes. Now sprinkle cheese on the other half. Put a lid on the pan and cook for exactly another 2.5 minutes. Done. Fold in half, put on plate. I know there are other methods out there, but this works for me.

Based on all my previous failures, I thought it would be hard. No, that’s not precisely correct. I thought it was one of those manual tasks that are tricky or complicated but with dedicated practice can be turned into muscle memory and made smooth and habitual. We can just round that off to “I thought it would be hard.” Nevertheless, I was wrong about that in any sense; making a good omelette turned out to be easy. I just needed some basic instructions.

Telling hard tasks from easy ones

Let’s give some operational definitions (as the psychologists say) for easy and hard:

Easy: after a small amount of effort or instruction, you can competently do the task.

Hard: it takes much effort or instruction to competently do the task. It might even be impossible for you to do.

When it came to making an omelette, I thought it would be hard but it was actually easy. So there’s four categories: things that look easy and are in fact easy, things that look easy and are actually hard, things that look hard and are actually easy, and things that look hard and are actually hard.

Maybe you are better than I am at figuring out which is which. This isn’t too scientific, but try out these six questions:

Q1: You can only know things if they are true. Sometimes you believe the truth by a lucky guess. You can’t get knowledge from a lucky guess, though. So what is knowledge?

Coming up with the right definition of knowledge is

a. Very easy

b. Easy

c. Somewhat easy

d. Somewhat hard

e. Hard

f. Very hard

Q2: The complexity of tasks is rated by how long it takes the fastest possible computer to solve them. Some tasks can be solved in polynomial time (P), others in nondeterministic polynomial time (NP). If the fastest possible computer can quickly solve the task, then it is a P task. If it cannot quickly solve the task, but the computer can quickly check a proposed solution, then it is an NP task. Can we either prove or disprove that P tasks = NP tasks?

Proving whether P = NP is

a. Very easy

b. Easy

c. Somewhat easy

d. Somewhat hard

e. Hard

f. Very hard

Q3: You get a job delivering newspapers. You have 100 customers that need morning papers. You want to figure out the most efficient route among them so you can save on gas.

Deciding on the best route to serve your customers will be

a. Very easy

b. Easy

c. Somewhat easy

d. Somewhat hard

e. Hard

f. Very hard

Q4. You go to the carnival and want to win a prize at ring toss. There are two dozen glass soda bottles on a table, and to win you need to toss a small ring over the neck of one of them. You have five tries.

Winning ring toss will be

a. Very easy

b. Easy

c. Somewhat easy

d. Somewhat hard

e. Hard

f. Very hard

Q5. Your mob boss has executed his archrival and ordered you to dig the grave. The boss hands you a shovel.

Getting the job done will be

a. Very easy

b. Easy

c. Somewhat easy

d. Somewhat hard

e. Hard

f. Very hard

Q6. Your 10th anniversary is next year, and you and your spouse are planning a once-in-a-lifetime trip to Italy. You decide to learn Italian before you go.

Becoming passably fluent in Italian will be

a. Very easy

b. Easy

c. Somewhat easy

d. Somewhat hard

e. Hard

f. Very hard

Here’s my prediction: the average person will think Q2 and Q6 are hard or very hard, and that all the rest are some kind of easy. That’s a problem, though, because they are all very hard. Defining knowledge is a major project in epistemology, and philosophers have been hammering on that one since Plato wrote Theaetetus. Proving whether P = NP is a famous open question in mathematics, and its solution comes with a million dollar prize. The newspaper delivery question is a math puzzler known as the Traveling Salesman problem, and is a computationally hard nondeterministic polynomial time problem. Carnival games, if not directly rigged, are designed to look much easier than they actually are. Digging a grave with a shovel alone may be physically impossible because of rocks, roots, and hardpan, and under the best conditions will require several hours and a strong back.

Here's a chart of tasks, sorted purely by my own intuition into the relevant quadrants. If I were less lazy I would design this as a real experimental psych study and recruit test subjects, but just see if you agree. This is meant to capture what’s easy and hard for the statistically average person. Yes, paraplegics will find jogging a short distance hard and Richard Burton will find learning new languages easy. But for the average person, here you go.

Why the false positives? Why do some easy things look hard? I think the explanation is half-assery. You try to do some basic home repairs without bothering to read the instructions or getting any guidance at all. Then things short out, fall apart, or look like garbage. Maybe you stall out a couple of times trying to drive a manual transmission and give up. Or, like me, you figure you can just naturally make good omelettes by instinct and when that fails you decide the task is, as my father used to say, too much sugar for a nickel. I tell my students that if you bomb an assignment, don’t give up—come to my office hours and we’ll figure out some effective study techniques or work through the difficulty together. It’s not as hard as it looks. Instead they’ll put in a half-assed effort, or even just a quarter-assed one and bail out.

When hard things look easy

More interesting is false negatives. Why do some hard things look easy? I can think of four possible explanations.

Sprezzatura. Some people make what they do look elegant, graceful, and simple. A doorman uses his fingers to whistle for a taxi 20 times a day with no effort or fatigue. Why couldn’t I? Roger Federer glides into a backhand like a supernatural god of tennis, flawless and omnipotent in his domain. How can I not think that I too might have a little taste of that? Oh, of course I couldn’t blast it like Roger, but surely I could hit a reasonably competent backhand with a little effort or instruction.

Easy to describe, must be easy to do. The idea that I should look for the most efficient route to deliver newspapers so I can save on gas sounds like an everyday example of practical reasoning. It’s in the same league as stopping at the corner Quik-E-Mart to get a gallon of milk on my way home from work, or figuring out what time we need to get on the road to make our dinner reservation. Same with describing someone you saw. It’s easy to grasp what the task is, and you think it can’t be that tough to say, “oh he looked like that guy in the movie we saw,” or “she had kind of a big nose and brown hair.” Knowledge? We all know what that is, it can’t be that challenging to define.

Not my problem, shouldn’t be anyone’s. If I don’t have a particular problem, then that difficulty must be easy to overcome. I eat food every single day, but I’m not obese. Sure, I admit that tortilla chips and salsa are my weakness, but I’m still not fat, so really, how hard can it be to lose weight? Just cut back a little and take the stairs instead of the elevator once in awhile. Overcoming heroin addiction, well, that looks brutal. I’m sure that if I tried heroin a couple of times I’d become an addict too. But smartphones? Obviously I have one like everyone else, but I’m not glued to cat videos and doomscrolling. I don’t know why people say they are addicted; all you need to do is go get some fresh air or read a book. Pretty simple, really.

Easy on the small scale, must be easy on the large scale. You’ve done something similar in a small way, so scaling up will be easy. Like, digging a small hole in loose topsoil to plant a tulip bulb is no big deal; digging a grave is just more of the same. Or, I took a couple of philosophy classes in college and thought they were an easy A. Surely becoming a philosophy professor is just a matter of taking a lot of philosophy classes and writing some term papers. Not too bad.

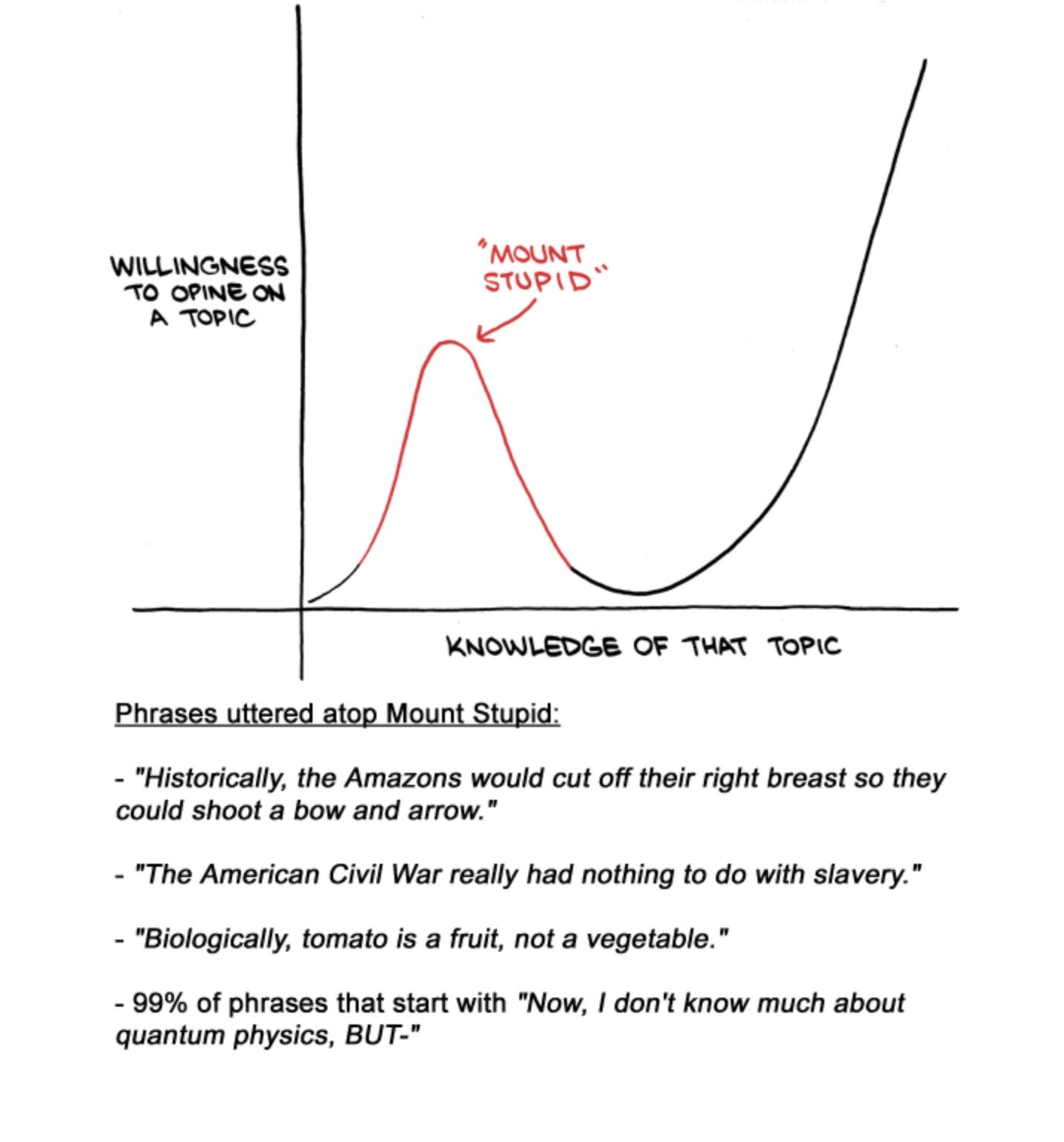

Why am I banging on about all this hard vs. easy business? Because I want to explain the Dunning-Kruger effect. Most people know that the Dunning-Kruger effect is when people with little competence in a domain overestimate their abilities. For example, give people a test on some topic and then ask them to guess how well they did. Poor performers tend to overrate their skills whereas high performers are much likelier to have a well-calibrated self-assessment, or even underestimate their skills. If we’re not good at a task we’re also bad at seeing that we’re not good at it. As David Dunning said in an interview, “The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club.”

There’s various efforts at explaining the Dunning-Kruger effect. None of them look too compelling to me. For example, one explanation is about a failure of metacompetence. D-K is explained by the fact that if we are first-order incompetent at something, that leads to being second-order incompetent at recognizing our first-order incompetence. It’s incompetence all the way up. Really, that doesn’t seem very explanatory to me, as opposed to just a restatement of the basic D-K thesis: we’re incompetent at recognizing our incompetence.

Here's what I think is behind the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Meta-hard and meta-easy

Some tasks are meta-hard (which sounds like a porno for English majors, I know): you can’t easily tell if you did them right. If you can determine right away that you did the task correctly, then it is meta-easy. For example, here are hard tasks that are meta-easy: assembling a 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle, ring toss, whistling with your fingers, solving an advanced sudoku, running a marathon, and digging a grave by hand. They are all hard to do, but you can easily tell if you did them properly. The meta-hard/ meta-easy classification cuts across the others.

Becoming a professional football player looks hard, is actually hard, but is meta-easy since you can see immediately whether you successfully did it. Proving Fermat’s Last Theorem looks hard, is actually hard, and is meta-hard because checking any proposed proof is difficult. Hitting a competent tennis backhand looks easy, is actually hard, and is meta-easy because it is evident whether the shot went in. Making a good omelette looks hard, is actually easy, and is meta-easy.

Finally we get to my central claim. The Dunning-Kruger effect kicks in for things that (1) look easy, (2) are actually hard, and (3) are meta-hard.

In Dunning-Kruger’s original study design they administered a test on topics like logical reasoning to their subjects and then had them estimate how well they did. Well, logical reasoning can be tricky, even when it looks easy, and there’s no obvious way to figure out if you did it correctly. Take the Monty Hall puzzle. The solution looks simple: it doesn’t matter whether you stick or switch. It’s 50-50. But the puzzler is famous because it is actually hard, and the correct solution is powerfully non-obvious and counterintuitive. It is meta-hard.

I really doubt we’re going to Dunning-Kruger people about tasks that look hard. Do people truly overestimate their ability to learn Russian, pitch for the Phillies, or overcome heroin addiction?

The easy-looking stuff is different. If you think finding a solution or performing a task is easy, the more you will overestimate your ability to do it. Furthermore, if the task is meta-hard, you won’t recalibrate your judgment about your skills because you’re not in a position to see right away whether you did it correctly. When something’s meta-easy, like sudoku, you could initially think “I’ll be really good at this” but after the immediate feedback of repeated failure you have little choice but to reconsider your skill level. Seeing the results of meta-easy activities leads to calibration. The Dunning-Kruger effect is being unskilled and unaware. With meta-easy tasks, you’re aware.

Take weight loss. It looks easy but is actually really hard. I think it is meta-hard as well. Weight loss is slow, nonlinear, and prone to reversals. There is no straightforward way to tell if your new diet and exercise regime will really be effective. If you stick with it for a couple of weeks and lose five pounds, is that proof of causation? Maybe you’ll just gain it back right away. Suppose we ask this question of a normal-weight person: “If you were overweight, do you think you would be good at dropping the extra pounds?” Probably they would think it easy and there’s not a rapid feedback mechanism to correct that judgment.

The explanation for Dunning-Kruger that I’m offering has a bonus feature. It also explains why very competent people either correctly estimate how difficult a task is for them to do, or they even underestimate their skill. It is because an expert knows just how hard the task really is and on top of that they know it is meta-hard. That’s what expertise brings along. They know that the job might look easy, but it is in fact very hard and even hard to know if you did it right. So they are more cautious in their self-estimations.

Understanding that Dunning-Kruger stems from the dangerous trifecta of looking easy, being hard, and being meta-hard helps explain why we're so stubbornly overconfident about certain tasks. The effect isn't just about incompetence breeding overconfidence—it's about the peculiar blindness that occurs when we can't easily verify our own failures. The omelette fallacy is a failure to calibrate what seems easy / hard with what is actually easy / hard. Once I had clear instructions and immediate feedback, the making omelettes shifted from apparently hard to actually easy, and from mysterious to obvious. But for truly difficult tasks that appear deceptively simple and resist quick verification—like logical reasoning, weight loss, or defining knowledge—we remain trapped in a pit of misplaced confidence. The expert's caution, then, isn't just humility or experience—it's a hard-won understanding that some tasks are triple threats: they're trickier than they look, genuinely challenging to master, and frustratingly difficult to evaluate.

Interesting post - and I like the distinction between meta-hard and meta-easy tasks.

I just ended up here after a link in an article that was just posted in a Dutch newspaper (paywalled): https://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2025/05/09/intellectuele-luiheid-a4892808

Very interesting. It explains why so many so called therapists or coaches claim to help people very well allthough they mostly help themselves in the first place and earn a lot of money... It is a blind spot and that’s why there should be more control or regulations about this phenomena I believe. Something like BIG registrations.