<rant>

I’ve read a lot of philosophy. Thousands of pages, scores of books, journal articles without end. I’m qualified to say this: 95% of it is absolute misery to read. I’m not talking about student work or amateur pontificating. I mean the actual professionals who write this stuff for a living. Here’s a random paragraph from a recent book:

[A]ttentive readers will have noticed that premise (DA-1) of the Direct Argument is identical to premise (IA-1) of the Indirect Argument. Henceforth, I’ll refer to this premise as ‘(DA/IA-1)’. Attentive readers will also have observed that (IA-2) and (IA-3) jointly entail (DA-2), whereas a proponent of (DA-2) needn’t accept either (IA-2) or (IA-3). In what follows, I’ll focus first on (IA-2) and (DA-2), saving discussion of (DA/IA-1) for later in this section. Finally, when discussing the Indirect Argument, I will make the friendly (to proponents of the Indirect Argument) assumption that (IA-3) is true. I’ll discuss and defend (IA-3) in Section 6.3.2 of the next chapter.

Here’s another from a different book:

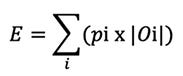

With the yield-potential moment of a possible outcome O is its probability-qualified yield |O|x pr{O}. And critical for the assessment of luck is the idea of the expectation (or “expected value”) of the chancy situation for the party at issue, as constituted by the total yield-potential of its various outcomes—the probabilistically weighted average of the outcome-yields that are involved:, as defined by:

The mathematical expectation E of a chancy situation is in effect a more sophisticated, “weighted” average of its outcome yields—one that takes account of the fact that their realization is not equiprobable.

I had to write reviews of both of these books for academic journals. Even though they were both books in one of my specialty areas, I suffered to read them. It was grinding, miserable self-flagellation the entire time, like banging my head on a rock. Jesus F’ing Christ, why must it be like this? Academic writing is the worst, and even academics who think they are good writers still suck, with the rare exception.1

Look, I absolutely get the need for jargon. Jargon is convenient shorthand for concepts that are familiar to experts. It keeps people from having to repeat the same long-winded thing over and over again. Here’s jargon that every epistemologist will know:

Adverbialism

Foundationalism

Coherentism

Contextualism

KK thesis

JTB

Barn cases

Gettier cases

Bank cases

Restaurant cases

Norms of assertion

Epistemic luck

Cleverly disguised mules

Envatted brains

Pyrrhonian skepticism

Demon skepticism

Cartesian certainty

The dream argument

Hinge propositions

Sense data

Closure principles

That’s a short list off the top of my head. Now, I think there’s a risk to using too much of this jargon, namely that it constrains our thinking. If we’re spending all our time in one conceptual playground, we’re likely to miss out on fresh problems and approaches. Even so, jargon has a legitimate role.

What I’m complaining about is the faux precision, the endless abbreviations for an author’s idiosyncratic definitions of quasi-formal expressions, the attempts to make things look mathy, as if a few symbols sprinkled into a paper sharpen the vagueness of life. I’m not saying there’s no role for formal logic or specialized locutions. But I will say that these are needed much less than people seem to think.

Confession: in one of my early papers I gave a syntax and semantics for adding two new operators to predicate modal logic in order to yadda, yadda, yadda. Anyway, I think I did something useful with that. However, it is also true that as a young scholar I felt like I had to prove my technical chops. That’s different from the search for truth.

Here’s another beef. Articles are sooooooo looooooogggg. Get to the point already and shut the hell up. Back when I was a wee tot in grad school, one of my senior professors gave this advice: a philosophy paper should be at most 20 manuscript pages. At 30 it should be a world-beating article. At 40 just write a book. Back then, in the days of monospaced fonts, a page was about 250 words. So he was saying to keep it under 5000 words. Oh boy has that ship sailed. Papers now are routinely 30 pages or more in manuscript. A 10,000 word paper is medium length. Articles in supposed short-form journals like Thought or Analysis are more like the average-length article from 40 years ago.

Why? Because authors think they need to address every teensy-tiny, picayune objection from every possible reader, all of whom will approach the paper with maximum malevolence. So half the paper is stage-setting, 40% is trying to forestall possible objections (or answer picky objections from the journal’s referees), and 10% is saying something new in needlessly jargony, technical language. Lord almighty, just tell me what topic you’re on about (10%), give me your new idea and positive arguments (80%) and stop me from making dumb retorts (10%).

You’d think “why not have some upstart journals who are really looking for innovative approaches that break this mold?” Oh, there are a few who say that’s what they are doing, but in reality they are lying liars who lie. It’s the same old series of courageous moves from stance A’’’’ to the brand-new never before seen proposal of A’’’’’. If you send in an article that’s “hey, everyone conceives of TOPIC this way, but I have an entirely new perspective,” the referees will beat on it until your novel idea looks like every other micro move in a decades-long debate, but now with 48 citations and 10 pages of answering potential criticisms. I’m saying this as a referee.

We do this to ourselves.

Philosophy has not always been this way. Great philosophy has not always been this way. There used to be a thousand different stylistic voices. Heraclitus wrote aphorisms. Plato wrote dialogues about how Socrates could argumentatively kung fu everyone in Athens. Lucretius wrote a poem—7400 dactylic hexameters!—on how terrific materialism is. Not your typical poetic subject, but there you go. Marcus Aurelius wrote a diary. Spinoza tried to write philosophy like he was writing proofs in geometry. Kierkegaard wrote under a dozen pseudonyms so nobody had any idea what he really thought. Sartre and Camus wrote philosophical novels.

Nietzsche had the greatest diversity of styles of any philosopher. He wrote aphorisms, extended essays, an intellectual autobiography, a quasi-religious book with characters and action, poetry, and critical papers. Imagine Nietzsche going to Oxford University Press nowadays with a book proposal for The Gay Science.

Proposal: I’m going to begin with several pages of poems that rhyme in German. After that, maybe a couple hundred pages on a bunch of random topics like how we need a philosophy of nutrition. I’m not going to give one, of course, but I’ll bring it up so lesser minds might pursue it later. I have stuff to say on women, the Germans, and Epicurus too. Then I was thinking about, I dunno, 30ish pages of pithy aphorisms. After that it will be a good time for me to announce the death of God and praise loving fate. Then another hundred pages on whatever crosses my cranium. Don’t worry, I have a big finish planned: “The Songs of Prince Free-as-a-Bird”! Now, what kind of advance were you thinking?

OUP would have security carry Nietzsche out and bolt the door behind him. Princeton professor and famed Nietzsche translator Walter Kaufmann described The Gay Science as “one of Nietzsche’s most beautiful and important books.”

That’s what philosophy used to be. We could make our words dance and spin. Why can’t we do that again?2

</rant>

Nietzsche once remarked that there were two good writers in the German language: Goethe and himself. He wasn’t wrong.

Writing on Substack is liberating. I can write in whatever style I damn well please. No tedious citations, no groveling before referee #2. This can be the agora.

Notice I didn’t even have to bring up Derrida to make these complaints.

By all means, let's go back to the days when we gave absolute SHIT arguments when we even bothered giving arguments. Let's go back to the times when it was hard to figure out the author's premises or conclusions, because they didn't bother to make them explicit. Let's go back to the days when we freely used terms in crucial claims that were multiply ambiguous even in philosophical discourse. Let's go back to the days when we just ignored objections that some philosophers might think are serious. Let's go back to the days when we offered thumbnail sketches of ideas, arguments, and the rest, instead of bothering to flesh them out to see if they are worthwhile.

Yeah, that will work.

By all means, let's be *entertaining* first, and thorough second. After all, it's not like we're at work here, when doing philosophy.

I like rants too, and I've heard this one, and been amused by it, for the whole 30 years I've been in philosophy. But it's much harder to write enjoyable but worthwhile philosophical prose than the post suggests. "Only articulate and respond to the good objections" is a common thought, but almost no one agrees with which objections are the good ones. If you want to avoid sloppy argumentation, then you're going to have to be precise--and precision will often require signposting and so on. If you want to treat an interesting and difficult topic with any depth, then it's probably going to take more than 7500 words.

Sure, we can point to a few great articles that managed to be relatively short, enjoyable to read, made a worthwhile point, and were pretty convincing. That's like saying we can point to some baseball games in which a player hit four home runs or threw a no-hitter.