The biggest complaint about LLM-style AI is that it makes stuff up. Gary Marcus is good at listing examples. Here’s a couple you can try yourself. I just asked Grok to tell me the meaning of “13 monkeys in a blender,” a nonsense phrase I just completely invented from whole cloth. Grok assumed it was a lesser-known idiom, and informed me that

The phrase could be interpreted as a vivid, absurd, or darkly humorous image meant to evoke a reaction, often used in casual or online conversations for shock value or to describe chaos. For example, it might be used to humorously describe a chaotic situation, like a messy or overwhelming event, similar to phrases like "a train wreck" or "herding cats." Without additional context, this is the most likely interpretation—purely figurative and not tied to a specific cultural or symbolic meaning.

The phrase appears in some online discussions, such as a Reddit post from the "cursedcomments" subreddit, where a user jokingly remarked about putting "13 monkeys in a blender" to see what would happen. This suggests it might be a meme-like phrase used in certain online communities to create absurd or provocative humor, often without deeper significance.

There’s a brief mention of "13 Monkeys in a Blender" as a possible band name or fictional entity in some online fiction platforms (e.g., a reference on a site called Booksie).

Absolutely none of that is true. I wondered if I had accidentally stumbled on an actual Urban Dictionary-type expression. But no, I found nothing by Google searching, either on Reddit or Booksie. Here’s another fun one. Ask for your own biography. Grok was detailed and accurate (if fawning), Gemini was adequate and accurate, but ChatGPT erroneously said I’m known for my work in both philosophy of religion and philosophical paradoxes, topics in which I have dabbled, but I am by no means a player.

These kind of mistakes everyone calls hallucinations, and we’re all obviously stuck with that term by now, but it is inaccurate. In The Principles of Psychology (ch. 19) William James writes, “An hallucination is a strictly sensational form of consciousness, as good and true a sensation as there were a real object there. The object happens not to be there, that is all.” AIs (so far) don’t have sensory inputs. They don’t experience non-existent objects. Closer is what James says in footnote 41 to chapter 19: “Illusions and hallucinations must both be distinguished from delusions. A delusion is a false opinion about a matter of fact, which need not necessarily involve, though it often does involve, false perceptions of sensible things.” AIs don’t hallucinate, they suffer delusions.

Why does any of this matter? Aren’t I just going on about trivial semantics? I don’t think so. Understanding the different ways things can go wrong will help us fix them; plus, I’m going to argue there’s a link between AI confabulation and the human kind.

Bullshit

It is tempting to accuse AIs of spreading bullshit, but I don’t think that’s quite accurate either. Harry Frankfurt’s classic definition of “bullshit” is that it is indifference to the truth. Liars know the truth and try to persuade their audience of the opposite. Bullshitters don’t know or care whether what they assert is true or false. An example is Trump’s recent claim that the Declaration of Independence—the divorce papers and middle finger the founders gave to King George III— is “a declaration of unity and love and respect.” Trump’s not lying. He just makes words come out of his mouth which may or may not have anything to do with reality and he doesn’t care either way.

Bullshit might be nothing but completely arbitrary, disconnected assertions. I imagine someone walking into a university library and reading sentences at random. “Nay, but to live in the rank sweat of an enseamèd bed, stewed in corruption, honeying and making love o’er the nasty sty!” “Last night, I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” “The world is everything that is the case.” “The quantity of matter is the measure of the same, arising from its density and bulk conjunctly.” Perfectly coherent, even famous sentences. But are they true? False? Mere poetry? Outdated? The latest thinking? A drunkard’s walk through the stacks, occasionally asserting whatever is close to hand, is just producing bullshit.

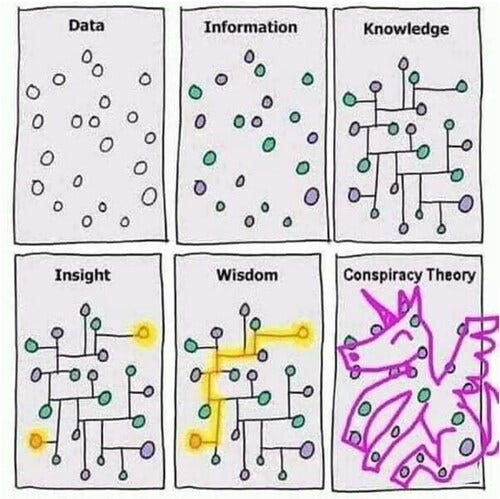

AIs aren’t spitting out random bullshit. What they deliver is orderly, methodical, and structured, and the mistakes they make nicely illustrate a classic philosophical problem. About 40 or so years ago there was a popular theory called “coherentism about justification.” The basic idea was that you are justified in believing some claim if and only if that claim fits into a network of beliefs, each of which mutually supports each other in a coherent and systematic whole. It’s not reasonable to believe novel claims when they can’t be integrated into all your background knowledge of how the world works.

Every epistemologist knows this traditional problem facing such coherentist theories of justification: schizophrenic delusions and wild conspiracy theories might be internally coherent but surely nobody’s justified in believing them. If AI “hallucinations” fit this pattern, neither they nor we are justified in believing them either.

AIs do possess facts about the world; they aren’t writing pure speculative fiction, and their systematicity shows it is more than stochastic bullshit.1 I think it is better to see their errors as connecting the dots between bits of data, as a way of filling the gaps. They are confabulating.

Confabulation

In cases of extreme amnesia the narrative recollection needed for a coherent sense of oneself over time disappears. Without that sense of temporal location, sufferers are adrift in a sea of experiences without landmarks or lighthouses. A common reaction of the mind to this catastrophe is confabulation: the spontaneous creation of meaning, pseudo-memory, and identity to plaster over the great chasms in one’s ordinary recall. People in sensory deprivation tanks are prone to hallucinations; the brain craves the input of new information to operate, and in the absence of any it goes ahead and invents the data itself. The confabulations of amnesiacs seem to be more of the same: without the sense-making groundwork of the past, the present is a blooming, buzzing confusion. So the mind invents a past to compensate for the one it has forgotten.

One cause of such amnesia is Korsakov’s Syndrome, the permanent loss of memory brought on by thiamine deficiency which itself is usually the result of chronic alcoholism.

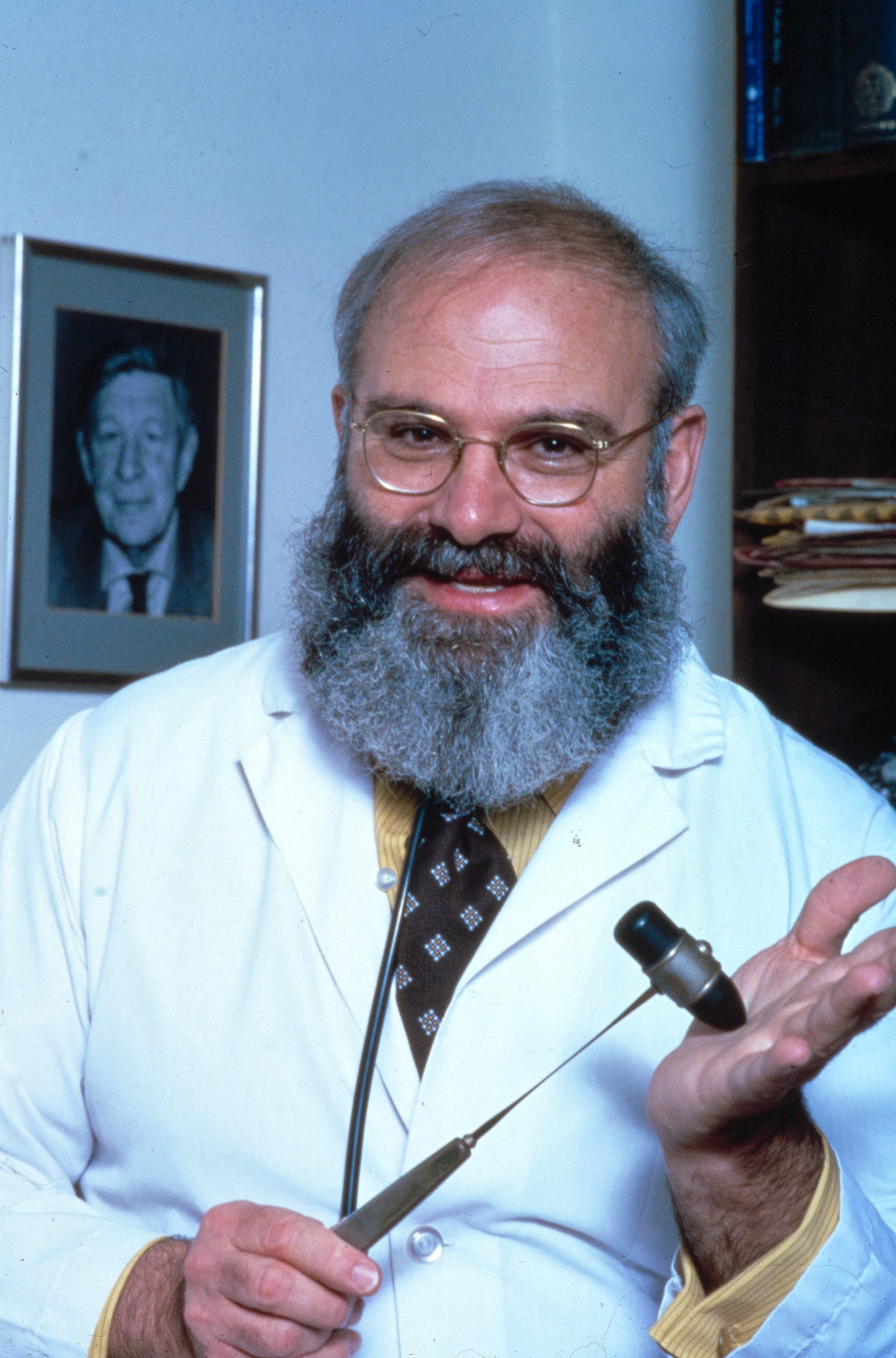

The great Oliver Sacks2 chronicled two of his Korsakov’s patients in his brilliant classic The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales. One of these, an ex-grocer named William Thompson, then Sacks’s patient in a neurological institute, would identify and re-identify Dr. Sacks in a matter of moments: Sacks was his customer at the deli counter, no—he was his old friend Tom Pitkins, no—he was Hymie, the kosher butcher from next door, no—he was Manners, a car mechanic from up the block, no—Sacks was a medical doctor that Thompson was just now seeing for the first time.

He remembered nothing for more than a few seconds. He was continually disoriented. Abysses of amnesia continually opened beneath him, but he would bridge them, nimbly, by fluent confabulations and fictions of all kinds. For him they were not fictions, but how he suddenly saw, or interpreted the world. Its radical flux and incoherence could not be tolerated, acknowledged, for an instant—there was, instead, this strange, delirious quasi-coherence, as Mr. Thompson, with his ceaseless, unconscious, quick-fire inventions, continually improvised a world around him… For Mr. Thompson, however, it was not a tissue of ever-changing, evanescent fancies and illusions, but a wholly normal, stable, and factual world. So far as he was concerned, there was nothing the matter. (p. 109)

Another wonderful example of confabulation is with amnesiac Clive Wearing. He suffered brain damage from viral encephalitis, leaving him existing moment to moment, without any sense of the past or future. In a documentary film made about him, Prisoner of Consciousness, you can watch Wearing confabulating in real time: sincerely and spontaneously “recalling” a fictitious past. Like William Thompson, Wearing’s crumbling edifice of the self is shored up with papier-mâché false memories, painted with enough detail that from a certain distance they look real.

Like amnesiacs, AIs, in their drive to unified, consistent word and world-making, confabulate information to fill the gaps into a seamless whole. My worry here is that we will piggyback on their efforts to do the same ourselves.

Specifically, I hypothesize that students will use AI to write papers and then believe that AI just enunciated the reasons they previously had for some position, when in reality they barely held the position and never considered any such reasons. Suppose they have some quarter-baked notion that they oppose selling one’s kidney on the open market. “Hey ChatGPT, write a 2000-word argumentative essay about why kidney sales are wrong.” Then they will read that output and nod along, “yes, those are exactly all the reasons I’m against kidney sales,” when in reality they had never thought about any such arguments at all. This is confabulation: falsely believing they had done the mental work themselves, convincing themselves that ChatGPT’s reasoning was their own all along.3

Brian Klass has written about status cheats, people who pretend to run marathons, or hire Strava mules to exercise in their stead while they bask in the kudos of their fake achievement. Or take Elon Musk, known for cheating at video games. Not your garden-variety cheat code cheating, or exploiting game mechanics, but (most likely) hiring Chinese workers to play games and give him the credit. Because, you know, not enough people worship him. The problem for Musk is that the nerds caught him out, thus preventing the nerd adoration he apparently desires.

Klass argues that status cheats are trying to improve their standing on positional social goods; it is all stolen valor. My concern is that when we cheat at thinking itself it is not others that we deceive, but ourselves. Like Thompson and Wearing, we will sincerely believe we had thoughts, reasons, inferences that we never had at all.

Playing Call of Duty does not give you actual military skills. Mastering Madden Football doesn’t qualify you to join even a Pop Warner league. Watching YouTube videos on woodworking does not make you a craftsman. GTA6 won’t make you a gangster. There must be engagement; you must do the work yourself. Even more, you cannot outsource your own thinking.

We all want to make sense of the world, of ourselves, of our pasts. I, at least, want that understanding to be grounded in reality. Compounding the confabulations of AI with our own is to build entirely in the air, to use Hume’s phrase. If we turn over our intellectual labor to AI, we cosplay our own lives.

I know the cliché phrase is to say that AIs are merely stochastic parrots, but after grading final exams this week I’m not entirely convinced human beings are doing much more.

Sacks is the GOAT of medical memoirists. I once had a brief correspondence with him many years ago, and I treasure the three-page handwritten letter he sent me.

If any psychologists want to test this hypothesis, please do!

I try to make the case in all my English classes that I teach that “writing is thinking,” but because thinking is hard work, many of my students don’t want to do it. And now after reading your essay, I see even more clearly with your comment about students having for example, Chat GPT, offload the writing and thinking needed to create an essay on an issue. They put the prompt into the LLM, it spits out an essay, they read it and they think “yeah I think that” but as you say, “in reality they had never thought about any such arguments at all. This is confabulation: falsely believing they had done the mental work themselves, convincing themselves that ChatGPT’s reasoning was their own all along.³”

I plan on sharing this essay with my students. I hope it makes a difference.

Hilarious- This is a superb essay. Connecting dots is what LLMs do, and "confabulate" is the perfect word for what happens when they do this in a way that goes haywire and misleads...