Twin mindsets: expansion and compression

Plus the metaphysics of the divine

I’m building a bookcase. It’s nothing too elaborate, just a built-in to occupy a niche next to a fireplace. But I had to make new baseboard molding and a few other fiddly bits. There’s a scale among woodworkers when it comes to using power tools. On the one end are guys (it’s usually, but not always, guys) who use whatever power tools they can afford and have space to store: a thickness planer, jointer, router, mortiser, drill press, drum sander, and table, band, and miter saws. Not to mention cordless drills, hammer drills, nail guns, a circular saw, jigsaw, track saw, belt sander, random-orbital sander, the list goes on. Then there’s the jigs, clamps, squares, and hand tools. I, uh, have most of that stuff.

On my end of the spectrum, it’s not so much a matter of acquiring new toys (ok, maybe a little), but the attitude that a purpose-made power tool allows for speed and precision in very specific tasks. I like making things, but also I’m not just in the shop to create sawdust—I want the bookcase at the end of it, sometime before I look like Gandalf.

The opposite approach is caveman woodworking. In the extreme, that means no power tools at all. It’s all handplaning, hand sanding, cutting boards with Japanese pull saws, and using a brace-and-bit drill. I’m kind of in awe of the really hardcore craftsmen who carve their own molding with complex handplanes and hand-chisel mortise-and-tenon joinery. At the same time I can’t help but think, why are you making this so hard? Like, you can afford to buy a dishwasher, why are you spending all your time at the sink with a scrub brush?

Compression mindset

The compression mindset is about maximizing efficiency by eliminating as much as possible. There’s a lot that is great about compression: you stop wasting time by finding a faster way to do something, learn a thing, get to a place. Spending time always has an opportunity cost, and compression is a rebate on those costs. If you plan your errands efficiently, you can get them done quicker and get home to do other things. When you have chores running in the background, like auto-paying fixed bills or running laundry or using a dishwasher, you can be doing something else while those chores autocomplete.

Using power tools in the woodshop is compression—they allow me to get that bookcase done in a reasonable amount of time and commence to filling it. Then I can move on to other projects. I made an endgrain basketweave cutting board earlier this summer, and if I had used the caveman approach I’d still be trying to flatten it with a jackplane that I needed to sharpen every 10 minutes.

However, there are two downsides to compression. The first is lossiness and the second is incompressibility.

Lossiness

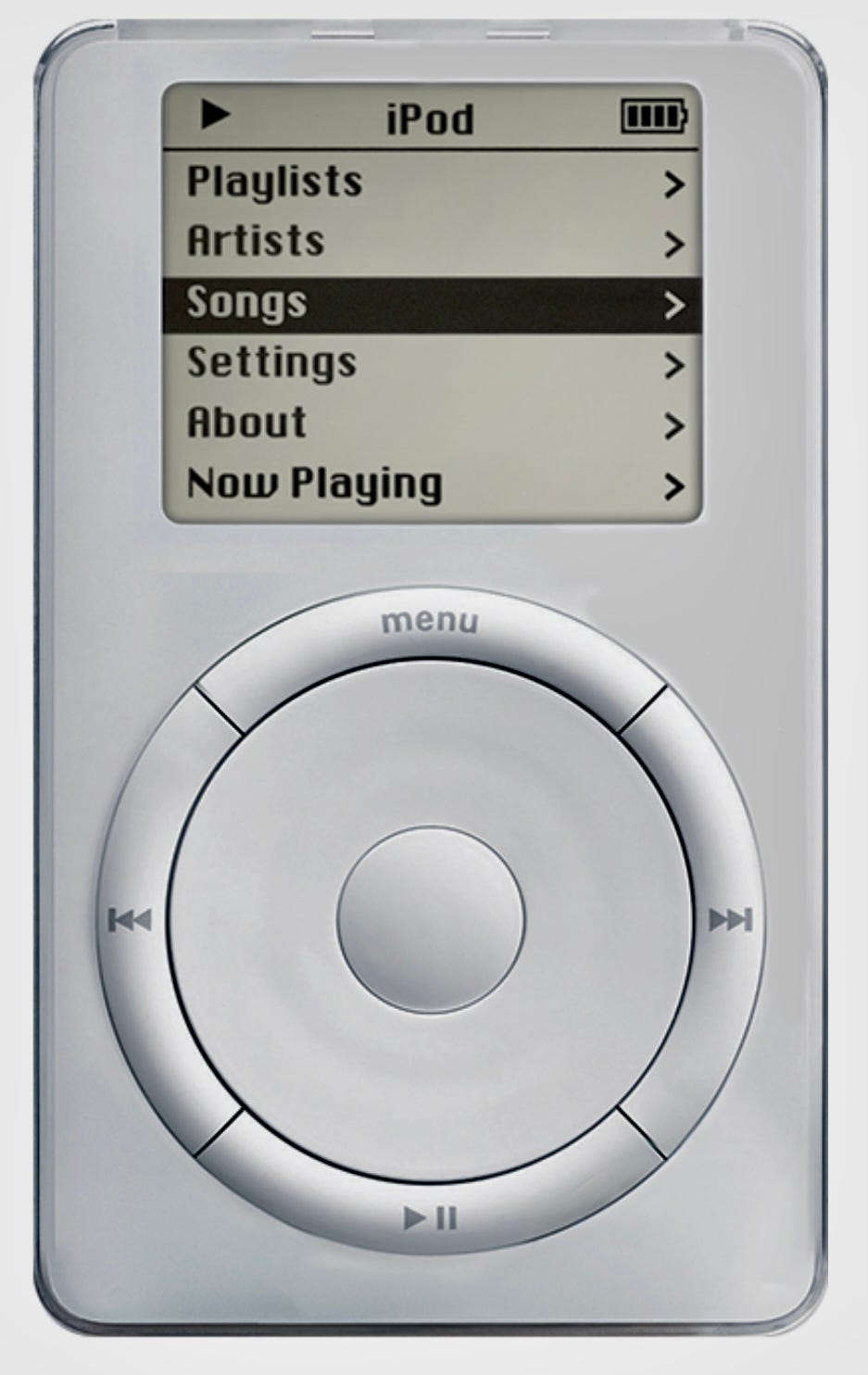

When the iPod first came out, storage was expensive and limited. The first ones had 5GB of storage. Apple bragged that that was 1000 songs! Well, it was 1000 lossy compressed songs. MP3s and Apple’s AAC encoding codecs make music files smaller by removing some of the data. If you’re listening to music on cheap headphones, in the car, or (nowadays) on your phone, you’re unlikely to notice the loss of fidelity. But do a direct A/B comparison of the same song in a lossy compressed format against an uncompressed file over a good quality home stereo, and you’ll hear a dramatic difference in audio quality. The MP3 or AAC sounds like it is underwater.1

In Persuasion, a college student recently asked, apparently without irony, “When the arguments of books can be summarized in minutes by AI, why read the entirety of a text?” Why, indeed. The answer is that the loss of fidelity matters, arguably even more than in the case of music files. Reading, particularly long-form prose, is an experience, and reading some LLM’s bloodless summary is a different experience altogether. In fact, let’s see.

I told ChatGpt to summarize War and Peace. Here is our interaction.

ChatGPT said: War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy is a sweeping historical novel set during the Napoleonic Wars, particularly between 1805 and 1812. It interweaves the lives of several Russian aristocratic families—primarily the Bezukhovs, Bolkonskys, and Rostovs—against the backdrop of war, social change, and philosophical introspection.

Key Plotlines:

Pierre Bezukhov unexpectedly inherits a vast fortune, struggles with his identity, and seeks meaning in Freemasonry, politics, and spirituality.

Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, a disillusioned nobleman and soldier, is deeply affected by war, loss, and love, especially after his wife’s death and his later romance with Natasha Rostova.

Natasha Rostova, a lively and impulsive young woman, matures through heartbreak, including a failed elopement with the charming but shallow Anatole Kuragin.

The Rostov family, once wealthy, faces financial ruin, symbolizing the decline of the old Russian nobility.

Historical Context:

The novel extensively covers the major battles of the Napoleonic invasion, especially Austerlitz and Borodino, offering vivid portrayals of military life and chaos.

Tolstoy blends fiction with real historical figures like Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I, critiquing the idea of "great men" shaping history.

Themes:

The futility and randomness of war

The search for personal meaning and moral integrity

The tension between free will and historical determinism

The transformation of Russian society

In essence, War and Peace is not just a story of war and romance, but a meditation on history, humanity, and the forces that shape our lives.

TL;DR. I’m a busy man! Why read the entirety of a text when it can be abbreviated? Let’s shorten things up some more.

I said: Summarize your summary

ChatGPT said: War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy follows several Russian aristocratic families during the Napoleonic Wars, focusing on themes of love, war, personal growth, and the search for meaning. Key characters like Pierre Bezukhov, Prince Andrei, and Natasha Rostova navigate personal and historical turmoil. The novel blends fiction with history and explores fate, free will, and the chaos of war.

I said: Summarize that summary

ChatGPT said: War and Peace is about Russian nobles facing love, war, and personal growth during the Napoleonic era, blending history with deep philosophical themes.

I said: Summarize that summary

ChatGPT said: War and Peace explores love, war, and personal growth in historical Russia.

I said: Summarize that summary.

ChatGPT said: War and Peace is about life in wartime Russia.

I said: Summarize that summary

ChatGPT said: War and Peace is about Russia.

I said: Summarize that summary

ChatGPT said: Russia.

Now we’re getting somewhere. Russia! I’ll just go ahead and check War and Peace off my to-be-read list. Done and done. In the beginning was the word, the logos, but at the end a word. All is compressed, made atomic, and fits into my pocket.

Incompressibility

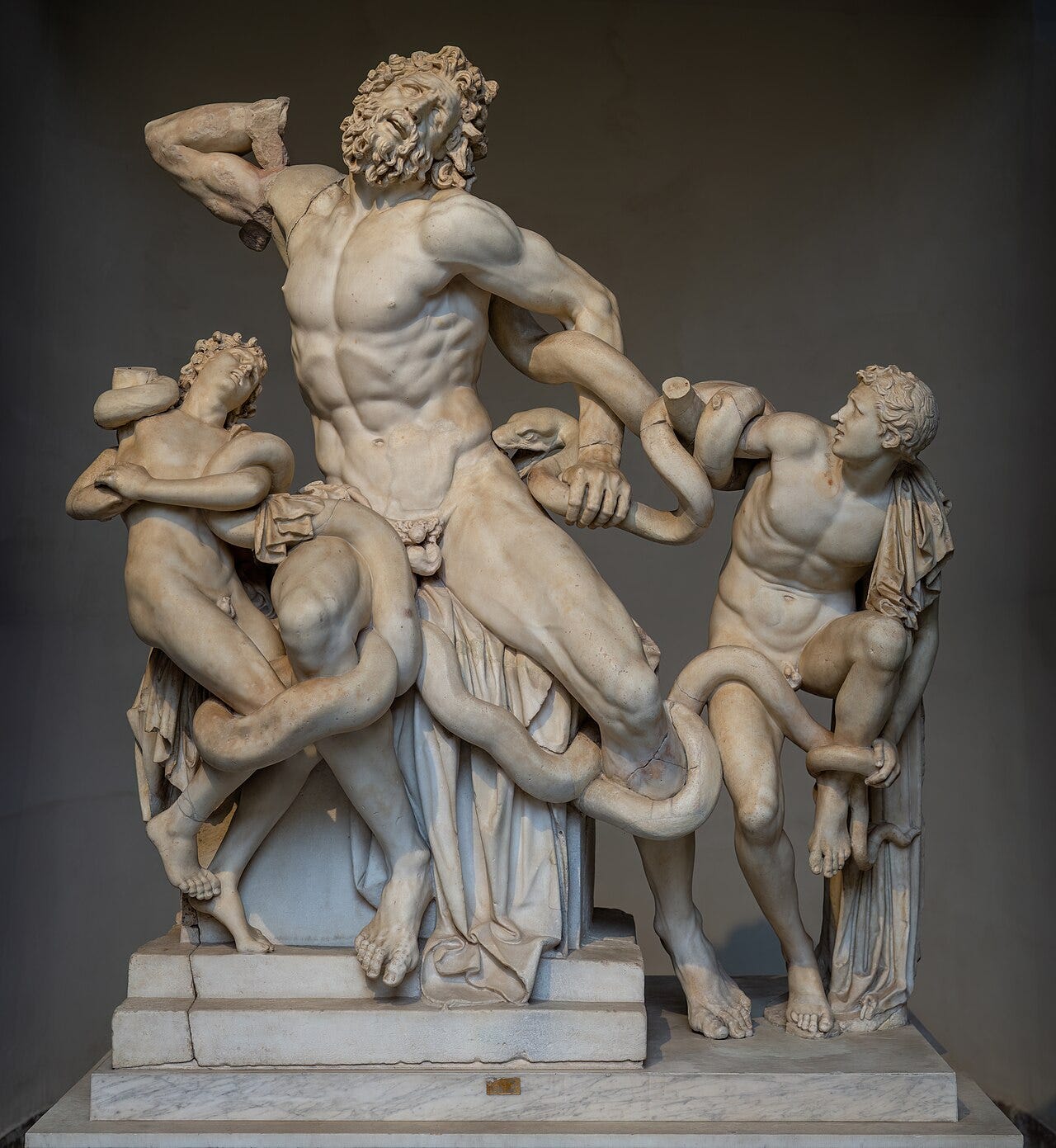

Many things are by their very nature incompressible. How would you shorten the experience of a painting? A statue? What bullet point list captures them? An experience can be described, but it is not the same thing. Tell me the timbre of a 12-string guitar; abbreviate the sound. Go ahead, explain the taste of coffee to someone who has never had it. At some point you just have to say, “Have a sip. It’s the only way to understand.”

So much is incompressible: relationships, symphonies, football games, poetry. An LLM summation of poetry makes it not-poetry; the poem is those exact words, no more, no less. Football games are four quarters, and anything fewer is not a complete game. The compression of a love affair is incomprehensible, and any attempt to do so is grotesque distortion, an OnlyFans funhouse mirror.

Expansion mindset

The expansion mindset aims to make our experiences slower, more precise, occupying every moment, each full of meaning. Events must take place over time and each part of the process is to be savored. Here we find caveman woodworking, where every tap on the chisel is a micron closer to the perfect fit. Here we find audiophilia, with the listener trying to hear the Platonic form of the sound in sonic heaven. The compression mindset wishes we could get all our nutrition from a gray protein bar; no prep, no cleanup. Expansion spends all afternoon in the kitchen on an elaborate slow food meal that fills the sink with pots and pans. For expansion, nothing is TL;DR. There are only books that you haven’t gotten to yet.

Expansion risks narrowness. When every hobby, task, and piece of learning deserves unending devotion, there are no limits. But we are finite and can only pursue a few things with such fidelity. As Chaucer wrote, “The lyf so short, the craft so longe to lerne.” When you have finally mastered the finest minutiae of Star Wars trivia, or every last approach to the Liar Paradox, how much brainpower, or even time is left?

Neither mindset is flawless. Compression and expansion each have different merits. In fact, they unexpectedly reflect different metaphysics of the divine. Bet you didn’t see that one coming!

In Disputation Against Scholastic Theology (thesis 17) Martin Luther writes, “Man is by nature unable to want God to be God. Indeed, he himself wants to be God, and does not want God to be God.”

What does it mean to want to be God? People talk about wanting to be a pampered housecat, or rich & famous, or a Jedi. They mean they want the qualities of a housecat, lazing around all day, not worrying about where their next meal is coming from. Or they want to wear robes and swing a lightsaber, or drive a Bentley to their yacht. To want to be God means wanting his traits as well.

The quality I’m interested in here is God’s eternality, his immortality. There are two traditional, and quite distinct, conceptions of God’s eternality, and each aligns with with the compression or expansion mindset.

The first is St. Augustine’s idea that God exists outside of time. He is eternal in that he can survey the entire timeline of the universe at once, like holding a book in your hands. Within the world of the book, actions take place in a chronological order, characters develop and take actions. The detective does not know who committed the crime on p. 10, but has figured it out by p. 300. But we readers, having finished the book, know all it contains. The same is true of a piece of music, or a film. They necessarily take place in time, and to properly appreciate them so must we. But we can also stand apart from their chronology. We are outside of book-time, and can flip to any page we like—all moments in book-time are the same to us, although not to the characters.

The second is the process theologians’ idea that God exists at every moment in time. God is within our timeline, but wholly present at each instant. All finite things only exist for some stretch of time, but the temporally infinite God exists for all of them. The alpha and the omega, and every Greek-lettered moment in between. Both God and ourselves are within time, it’s just that while we may be at many moments, he is at them all.

So how does this connect to compression and expansion?

The compression mindset is that of Augustine’s God. Compression maximizes efficiency by eliminating whatever it can. To be outside of time altogether is to eliminate time itself. Omniscience has compressed all facts of the world into the single Big Book of Reality, and every event from the God’s Eye perspective is simultaneous. The compression mindset advises that we speed up, become more efficient in getting from A to B. Nothing is faster than simultaneity. Outside of book-time, where the temporal order in the Big Book of Reality means nothing at all, God achieves perfect compression.

In our world only Tolstoy can unpack “Russia” into War and Peace, but Augustine’s God, outside of time, can do the same. The true endpoint of compression is to have condensed everything into a single comprehensible drop.

The expansion mindset is that of the process theologians’ God. Every moment is imbued with value, each instant is meaningful and an opportunity for perfection. How can we take shortcuts when this, this now, is wholly beautiful? With eternity you have all the time in the world to delve down any appealing rabbit hole, spend 10,000 years reading every book in the library, master every craft, get a 100 PhDs, and learn the smallest bits of trivia. The final aspiration of expansion is to stretch out, to fill every minute as full as possible. You can spend as much time as you like on anything, because you literally have all the time in the world. It is an endless resource.

We may all want to be God, as Luther claims, but whether we are drawn to compression or expansion tells us the form of our aspirations to the divine.

Streaming services like Spotify also rely on lossy compression.

Utterly insightful, Stephen. I and doubtless many others did not anticipate your final links to the divine. This is a most creative leap.

But I dare say in the lived experience of these operational tensions between expansion and compression, those of us inclined to theism may similarly shift between Augustinian compression and process-theology expansionism. In other words, both — not just on or the other. A third operational option is of course a mindlessly oblivious “just do it” approach. The latter conceals a morass of suppressed, time-conscious impulses one may try hard to ignore psychologically in order to stay focused on the current task. Probably a common form of so-called willful ignorance.

'As Chaucer wrote, “The lyf so short, the craft so longe to lerne.”'

In the spirit of compression, the Romans excelled. "Ars longa, vita brevis".

Or in the earlier version attributed to Hippocrates:

"Ὁ βίος βραχύς, ἡ δὲ τέχνη μακρή".