Here’s something I’m willing to bet: that you think you have a right to your own opinion, or everyone is entitled to their own opinion, or something similar. Well, I have bad news. You’re not entitled to your own opinion, and I’m going to explain why.

First, let’s get clear about what’s on the line. Sometimes when people say they have a right to their own opinion, they mean they have a right to express their opinion. Now, expressing your opinion is an action, and actions might be regulated, restricted, or otherwise subject to the law. If you have a right to express your opinion, then you can say what you want without the government prosecuting you for it. Well, there’s nowhere on Earth where that’s an unrestricted, absolute right.

In China it’s illegal to use the internet to overturn the socialist system1, in Saudi Arabia it is unlawful to insult the prophet Muhammad, and in Sweden you can’t heckle members of Parliament. Several countries have strict penalties for insulting their national anthems or desecrating their flags. Even in the USA, where freedom of speech is enshrined in the very first amendment to the Constitution, you can’t threaten people, incite violence, commit fraud, slander others, violate intellectual property rights, and various other things along this line. Apart from the law, there’s plenty of socially-enforced limitations on speech, as the heckler’s veto, cancel culture, and deplatforming show.

So do you have a right to your own opinion in the sense of being able to say what you want without penalty? Kinda sorta, with a lot of codicils and regional restrictions. Taken in an absolute, unfettered way, no.

There’s another sense to you have a right to your own opinion, though, which I think is more interesting:

It’s OK to believe whatever you want.

Regardless of whether the government (or your boss/neighbors/protesters) might crack down on you for expressing your beliefs, is it all right for you to believe whatever you choose to in the privacy of your own mind? Before you say yes, notice that the following proposal looks awfully similar:

It’s OK to do whatever you want.

I’m hoping you’ll think that’s not true. It’s not OK to do whatever you want for a pretty simple reason—some things are just wrong to do, and it is not OK to do wrong things. You know, that whole morality business. You could still do those wrong things—perhaps no one’s stopping you—but you would be making a moral mistake. Analogously, maybe there are things that you should not believe. You could believe those wrong things anyway, but if you do, you would be making a mistake. I’m not claiming it is a moral mistake to believe the wrong thing. I am claiming it is an intellectual mistake.

Truth seeking vs. pleasure seeking

So what kind of things are wrong to believe? False things. It is an intellectual mistake to believe false claims. You should not believe them. Here’s a principle to consider:

Truth seeking: you should gain truth and avoid error.

You’re probably itching to ask, “yeah, but how can we tell the difference between what’s true and what’s false?” An excellent question without an easy answer. To quote Karl Marx, “There is no royal road to science, and only those who do not dread the fatiguing climb of its steep paths have a chance of gaining its luminous summits.” But before we talk about those steep paths, we should be sure that Truth Seeking captures the goal we really want.

It’s tempting to argue that Truth Seeking is wrong because sometimes mistakes are useful and by messing up we can figure out what the right thing really is. In which case we shouldn’t avoid error at all. Making errors is a useful step along the road to the truth, because we learn from our mistakes. It’s like if you’re learning to play tennis—you hit a lot of shots out before you learn to hit them in.

That’s not a good objection, for two reasons. (1) Plenty of people believe idiotic things their whole life long and never learn from their mistakes. In fact, there’s evidence that people learn less from mistakes than success. Let’s try to buck the trend, and learn from the mistake that people learn from their mistakes by realizing that they don’t and mistakes are bad. (2) Even if errors are inevitable and people do learn from their mistakes, they don’t want to make those errors. The objective is to get rid of false beliefs and gain true beliefs. Look at the tennis analogy again: the goal is to hit your shots in and not hit them out, even if you miss a bunch while learning the game.

Here’s another challenge to Truth Seeking. Who really cares if what we believe is true or false? If you want to believe that QAnon has the secrets of what’s really going on instead of just being trendy LARPing, then go right ahead. Bigfoot, space aliens, conspiracy theories, cult leaders—well, they keep life interesting, don’t they? Believe them if you want; you might as well have some fun in your 80 years here.

Let’s put it as a principle:

Pleasure Seeking: You should believe whatever makes you happy.

Pleasure seekers aren’t opposed to the truth, they’re merely indifferent to the truth. In Harry Frankfurt’s classic formulation, they are bullshitters. If the truth makes you happy, then great. If falsehoods do, then they are just as good.

Intrinsic and instrumental value

The dispute between truth seekers and pleasure seekers really comes down to this: does the truth have intrinsic value or does it only have (at best) instrumental value? The stuff that has intrinsic value is what you want for its own sake, not because it leads to or produces something else: love, art, music, flourishing, pleasure. Asking “why do you want pleasure?” is mostly going to elicit a confused look. It’s good? I like it? I mean… what else is there to say?

Things with purely instrumental value you want because they help you get something else. A plane ticket is instrumentally valuable because it helps me get the hell outta Dodge, but I don’t want a plane ticket just because I like tickets. Money is instrumentally value because it allows me to buy things with intrinsic value; I don’t want money because I have a fetish for rectangular pieces of green paper.

We have two options:

The value of truth is intrinsic. Truth is valuable in itself, for its own sake, regardless of whether knowing it produces happiness or any other valuable thing.

The value of truth is instrumental. Truth is valuable because knowing it allows us to survive, achieve our goals, and makes us happy. That is, the truth is no more than a useful tool to help us get what has intrinsic value. Having the truth doesn’t really matter so long as there is no downside to false belief and believing makes you happy. There’s no point in caring about truths that lead to unhappiness; in fact in those cases it’s better to believe in a nice soothing lie.

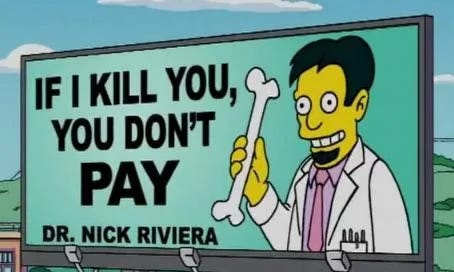

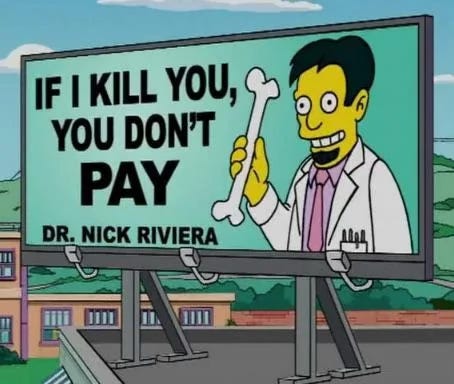

It could be both—maybe having the truth is valuable in itself, but it also leads to other good things. I think it’s pretty obvious that the truth at least sometimes has instrumental value. When picking mushrooms for dinner, knowing how to spot the differences among chanterelles (delicious), amanita phalloides (poisonous), and amanita muscaria (hallucinogenic) is a valuable skill to have. Knowing the truth that your prospective surgeon trained at Hollywood Upstairs Medical College instead of Johns Hopkins is probably useful intel as well. The question is whether the sole value of truth is instrumental.

Here’s an argument for why truth is intrinsically valuable. See if you agree. It starts with a thought experiment. Suppose your significant other is cheating on you. On the regular. Now, the future could go down one of two paths:

You find out about the cheating. The usual recriminations, crying, accusations, arguments, blowups, and breakups ensue.

You never find out about the cheating and nothing bad ever happens. To be clear, no one gets an STD, no one gets pregnant, there are never any rumors or suspicions, and from your perspective, everything is both hunky and dory. Nothing bad happens.

Which future do you want? If you want future (2), in which your partner keeps on cheating and your never find out about it, then you think that the value of truth is solely instrumental; it is only good to have the truth if it produces something useful or valuable for you have, like happiness. However, I’m predicting that you want future (1), even though in that scenario only bad things happen. If you want the truth about your cheating partner anyway, it is not because having that truth makes you happy. It’s because you want the knowledge nevertheless, for its own sake. It’s because the value of truth is intrinsic.

None of that means you find every true belief valuable. There’s plenty of things nobody really cares about, like how many blades of grass are in your lawn, or whether the number of stars in the universe an even number or an odd one, or how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. Still, if for some reason you really wanted to know how many blades of grass were in your lawn, presumably you would want the true answer. Otherwise, not having an opinion at all is probably the way to go.

The main argument

Bringing everything around full circle, here’s why you don’t have a right to your own opinion.

If truth has intrinsic value, then you should prefer Truth Seeking to Pleasure Seeking. (Reason: Duh, intrinsic value. Remember what you wanted in the infidelity case?)

If you should prefer Truth Seeking, then it is wrong to believe false things. (Reason: the principle literally says you should gain truth and avoid error, and you are in the wrong if you don’t do what you should).

If it is wrong to believe false things, then it is not OK to believe whatever you want. (Reason: C’mon, that follows pretty directly).

If it is not OK to believe whatever you want, then you don’t have a right to your own opinion. (Reason: because your fundamental intellectual duty is to seek out and believe the truth).

So long as truth has intrinsic value, you don’t have a right to your opinion. Your opinion isn’t sacred. It doesn’t deserve respect just because it’s what you believe. You might believe in bullshit, after all. Me too! That’s why we need to do what we can to gain truth and avoid error. We should all be Truth Seekers.

The Chinese DeepSeek AI won’t even discuss controversial political subjects or topics that make the Chinese government look bad.

I don’t buy the premise that “If truth has intrinsic value, then you should prefer Truth Seeking to Pleasure Seeking.” You state in your post that pleasure also has intrinsic value. Thus, the fact that truth has intrinsic value does not in and of itself put it above pleasure in terms of value.

You could argue that while both truth and pleasure are intrinsically valuable, truth is more valuable on balance—which your thought experiment about adultery might appear to demonstrate.

But just because truth is more valuable than pleasure in specific examples or thought experiments doesn’t mean it’s universally more valuable in all scenarios. There are various scenarios in daily life in which white lies promote the stability of a relationship or strategic deceptions protect the safety of a country, for example.

As a side note, the fact that we are able to talk about whether truth or pleasure is more important in a given scenario may indicate that our usage of the term “intrinsic value” is a bit loose, since such a comparison requires comparing their values in terms of some third measure of utility that is even more intrinsic.

Good piece. Thanks. I’m a big proponent of truth, I’m just never sure if I actually have it, or if I just have something I wish were it.

Along those lines, I think more people than you might imagine would keep their happy marriage alive at the expense of not knowing everything their spouse does that would make them seem significantly less appealing (including cheating). There’s often a lot of denial surrounding infidelity because there are so many other factors to consider in the value of such a partnership.