I just had a birthday. Not a milestone, although my next one will be. I’ve found myself thinking a lot about who has had the biggest impact on my life. Apart from family, it has been two old men. For them I am immeasurably grateful. Here’s some stories.

Roderick Chisholm

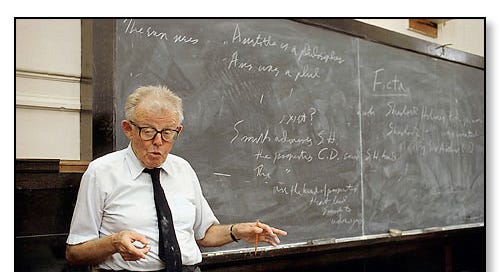

I met Rod Chisholm my first semester as a graduate student. He was 71. His reputation was enormous; certainly he was the most famous living epistemologist. I was 50 years younger, a country kid from Texas who barely knew Plato from a potato. I was in awe of all of my professors, but especially “Rod the god,” a rumpled deity in a powder-blue sportscoat floured with chalkdust.

Sometimes junior faculty sat in on seminars taught by the other members of the department, but the senior faculty (especially Jaegwon Kim and Ernie Sosa) sat in on Chisholm’s seminars. I eventually called all my other professors by their first names, but Rod was always “Professor Chisholm.” Anything else just felt disrespectful.

That first semester all us new grad students signed up for Chisholm’s Metaphysics course. One of my cohort already had a master’s degree from another university, and I was intimidated by him— I figured he was way more prepared for philosophy bootcamp than I was. It turned out we were really in the same boat.

At the beginning of one class, the master’s guy asked if he could come to the chalkboard. He was all eager to show some argument he had gotten from Nelson Goodman, confident that this Goodman thing was going to rebut a point of Chisholm’s from the previous class. Chisholm said, sure, come on up. Master’s guy walked to the front and confidently wrote out this detailed, multi-premise argument. Chisholm looked at it for a minute, and calmly said, “hmm, what about this?” And gave a one-liner counterexample that completely demolished the whole thing. The master’s guy sheepishly replied, “Oh. Yeah. I guess that’s right,” and sat back down.

Meanwhile, I’m writing in my notes, “do not mess with the old man.”

There were a lot of colloquium talks from visiting speakers: Derek Parfit, Hilary Putnam, people like that. Chisholm didn’t always go, but he would turn up if one of his friends was speaking. One time we had William Alston giving a talk on perception, and Chisholm was in the audience. During Q&A, Chisholm asked, “Bill, if my students ask me ‘is Alston’s position P & not-P’1 can I tell them yes?” Alston replied, “yes, that’s right.” Chisholm, having extracted a mic-drop contradiction from the speaker, courteously said, “thank you,” and left the room. The audience burst into laughter.

Chisholm taught us to do philosophy by example. Nothing was a dead theory in his classes; everything was an active, vibrant puzzle to wrestle with. I took an Intentionality seminar with Rod, and he handed out a fairly ambitious syllabus covering several topics. However, his approach in class was to pursue an issue until we solved it, then move on to the next one. All us students were practicing our critical chops, though, so we never let anything go. We’d write him three-page critical letters after class on top of our assignments (which he always dutifully answered). As I recall, we got through one and a half topics in that Intentionality seminar, and we only got past the first one because we were all burned out on it and gave up. But we learned very deeply how to do philosophy.

An example of Chisholm’s generosity is these comments he wrote on a short paper of mine critiquing one of his views. To be clear, my criticisms were about like telling Sir Christopher Wren that one of the shingles on the roof of St. Paul’s was a little loose. Nonetheless, Rod wrote this:

I was the last student whose dissertation Chisholm agreed to supervise. He was a sure hand at the tiller. Three standout memories: (1) the day he agreed to advise me, and I left his office walking on air; (2) the day he told me not to start any new chapters (my plan had been to keep writing until told otherwise); and (3) the day I passed my oral defense and he came out into the hall where I was anxiously awaiting the committee’s verdict, shook my hand, and said with a smile “congratulations, doctor!”

Some years later, when I learned that Chisholm was in poor health, I called him on the phone. I wanted to ask after him, and to reassure my old master that I was now safely ensconced in a tenure-track job. I had made it after all. I instinctively knew it would be our last conversation. At the end, when I finally choked out “goodbye professor,” I wept.

Daniel Knowlton

My father collected Heritage Press books. Heritage Press was the more budget version of The Limited Editions Club, a major 20th century fine press. While in grad school I got interested in LEC books, and found a copy of their 1934 edition of Frankenstein for cheap at a used bookstore. Cheap, because the leather spine was falling off. I got to wondering if I could find someone to repair it and started to ask around. I learned that one of the university’s rare books libraries had a hand bookbinder on staff with a bindery in the library basement, and maybe he could help. Book in hand, I trudged down the stairs and met Dan Knowlton. Dan was 67.

Dan assured me that he could re-spine my book to match the original for some absurdly low fee. He saw my interest in books and in his plans for repairing Frankenstein, and told me that he offered lessons in hand bookbinding at his home studio. I signed up on the spot.

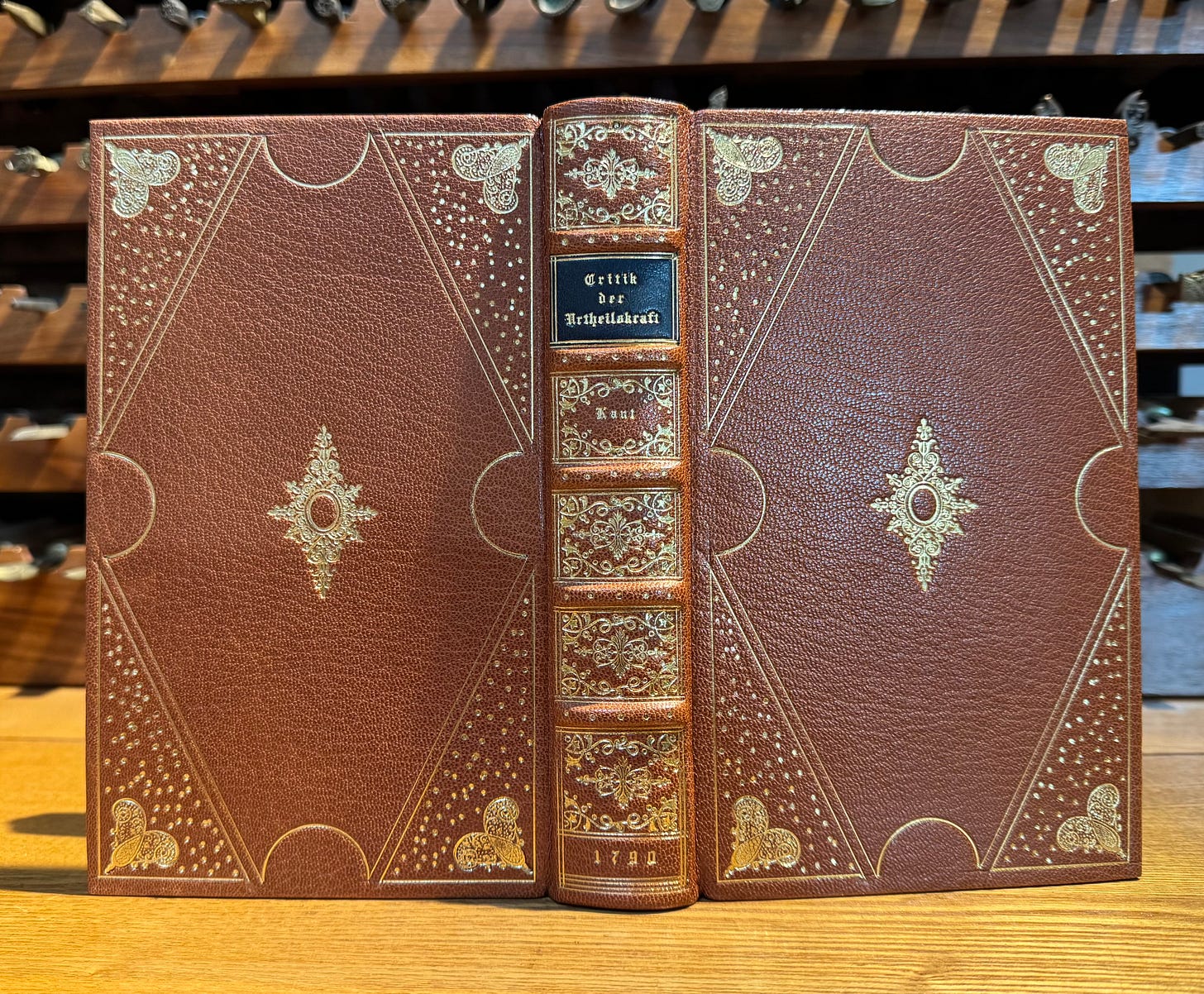

For two years I drove to Longfield Studio to study with Dan. He had hand-built his bindery as an addition to his home. Entering felt like stepping out of a cold late 20th-century New England winter into a cozy and warm workshop of 1790.

The Franklin stove was alight with hardwood, and the high-beamed room was crammed with iron presses, oak type cabinets, a paper guillotine, board shears to cut dense cardboard for book covers, goatskins and calfskins in multiple colors, books of gold leaf, rolls of gold foil, and stacks of marbled and fine art papers. At the opposite end from the stove was an enormous wood and iron French standing press that should have been in a museum. Dan’s collection of intricately cut brass hand tools for gold decoration were in themselves a history of the book. The middle of the room contained a long table around which his half-dozen pupils worked. Halfway through each three-hour class Dan’s wife Nina would appear with tea and biscuits.

A bookbinder’s bread-and-butter is thesis binding for students and fixing up old family Bibles. These are not generally opportunities for extravagance or creativity. On the first day Dan brought out a few of his masterpieces, I think to show us what was possible and what we might aspire to. One was a first edition of Huckleberry Finn, bound now in full crushed goatskin, with different colored leather squares inlaid to the boards in a checkerboard pattern sporting fine gold tooling. Such a thing seemed an impossibility to a complete novice still awaiting instruction on how to kettle-stitch signatures together.

Dan was patient and encouraging, with no more than a pained “ohhh” by way of criticism, and then only when I did something really dumb. The feeling of working with my hands on a material, concrete project was rewarding in a way that was completely unlike my daily toil in the abstract realm of ideas. I have stuck with bookbinding ever since. I can only hope that Dan would be proud.

In The Will to Power, Nietzsche wrote that the only true nobility is the aristocracy of blood. Knowing this would be easily misunderstood, he added a parenthetical comment that he was not talking about the Almanach de Gotha, a genealogical account of the royal and princely houses of Europe. Instead Nietzsche claimed Heraclitus, Empedocles, Spinoza, and Goethe as his ancestors, and wrote “when I speak of Plato, Pascal, Spinoza, and Goethe, then I know that their blood rolls in mine.” Our intellectual and spiritual forebears are every bit as important as our genetic ones.

Dan Knowlton’s teacher was Marian Lane, and her teacher was Francis Sangorski, one of the greatest bookbinders in history. Through Chisholm my ancestors are William James, Charles Sanders Pierce, Immanuel Kant, and Gottfried Leibniz.

While I am a lesser son of great sires, I am descended from kings. For such ennoblement, my gratitude is boundless.

That’s what it sounded like to me.

I envy your time with these men.

Great essay, doctor! Coincidentally, one of my great professors as an undergraduate was Chisholm's last PhD student :-) Rod the God would be proud of his student, I've no doubt.

I'd like to hear more about the Alston story. Alston was one of my grad professors and I can't picture him admitting to a contradictory set of beliefs.