If there is one single thing that all Americans agree on, it’s that the government wastes money. That, in fact, might be the only thing we all agree on. I’m here to deliver some good news: everyone is wrong! So get along, little DOGE. There is no such thing as government waste, not really, and I’m going to explain why not.

Efficiency vs. slack

Slack, not waste, is not the opposite of efficiency. Slack is excess capacity allowing for responsiveness and flexibility; it is the absence of binding constraints on behavior. It’s when there is enough elbow room for experimentation, invention, exploration. Slack is freedom and insurance against disaster.

Perfect efficiency in your household budget would mean that for all and only dollars you earn, you spend those dollars before your next paycheck. There’s never unused money building up, and you never go into debt. You run the tightest of all possible tight ships. Obviously this approach is a calamity—it is the very definition of living hand to mouth, paycheck to paycheck. You have no savings, and are therefore vulnerable to any kind of risk. If you lose your job, or get sick and can’t work, then you are screwed; you have no cushion to fall back on. Savings are slack.

Perfect efficiency in business means running companies as lean as possible, with no redundancy in employees, no stockpiled parts, and no backups for mission-critical systems. A company run this efficiently is fragile. A glitch in the supply chain and everything crashes to a halt, or a key employee gets hurt and no one else can run the line. Redundancy is a kind of slack.

I see this in academia all the time: politicians constantly insisting that we “tighten our belts” and “trim the fat.” My university is already lean to the point of anorexia, but for some reason people think there’s always fat to cut. Any backyard pit master knows that if you trim 100% of the fat off your brisket, it will be dry and flavorless. Of course you cut away the big hard white chunks in advance, but fat is flavor and you want the end result to be juicy and tender.

Too much slack is demotivating. If you have millions in the bank, then why work at all? If you are one of a dozen mid-level managers doing basically the same thing, you know somebody will pick up any ball you drop, so you might as well take three-hour lunches. The secret is having just the right amount of slack, finding that balance between total efficiency and drive on the one hand and complete slack and undirected freedom on the other.

The government also needs slack to meet unexpected emergencies or deal with unforeseeable events on the world stage. If we run the government with perfect efficiency, then there’s no excess capacity when the next Katrina hits, or there’s another pandemic, or somebody starts up a war. How much slack do we need? This is precisely what we should be debating! Reasonable people of good faith will arrive at different conclusions, and that is completely fine. But we cannot merely point to inefficiencies in government and declare that they must be abolished. They could just be valuable slack.

Services vs. business

I often hear that we should run the government like a business. This is one of those dumb things that is constantly repeated like some new hot take. It is a pet peeve of mine that any social organizations with some kind of business element are treated as simply another corporation. Churches must pay priests, ministers, secretaries, and sextons, but that doesn’t make them merely a business like any other. The Pope doesn’t have an R&D department developing a new savior. (Now with more halo!) Surgeons, nurses, professors, teachers, and support staff all need to eat, but medicine and education aren’t just businesses that you might or might not patronize. Everyone needs some at some point. How about the military? The soldiers all earn a paycheck, but I don’t remember the Army ever turning a profit.

The government is not a business either. Taxpayers give the government money to provide services. In the language of the Constitution, it is “to provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” That’s nice and open-ended, but nowhere mentions a profit and loss ledger.

What services should the government be providing? On the contractarian picture, broadly we’d like the government to solve problems that individuals can’t work out on their own, like collective action problems and coordination problems. It’s here to keep us from backsliding into the state of nature and Hobbes’s famous “bellum omnes contra omnes.”

All right, but what specifically should we (through the government) spend our money on? Surely there’s a bunch of stupid stuff in the giant federal budget. You know, like

Funding drag queen rainbow story hour for young tots: “How Jack Became Jill.”

Equipping ICE with autonomous drone killbots armed with depleted uranium-tipped heat-seeking missiles.

Installing a 14k gold urinal in the Oval Office bathroom.

Training steelworkers to unpack their invisible knapsack of privilege.1

The point is that in a democracy, we should be debating exactly what services we should purchase, and what best promotes the general welfare. Obviously there will be noisy disagreement about pretty much everything. In addition, thanks to Simpson’s Paradox, a majority of government programs are supported by a majority of voters, but it is also the case that more voters want to shrink the government. That’s not inconsistent: it’s just that different coalitions support different programs, and each is a simple majority of voters.

We’ll naturally call each other’s preferences a waste of money, but there is no objective waste on this picture, just ideological choice.

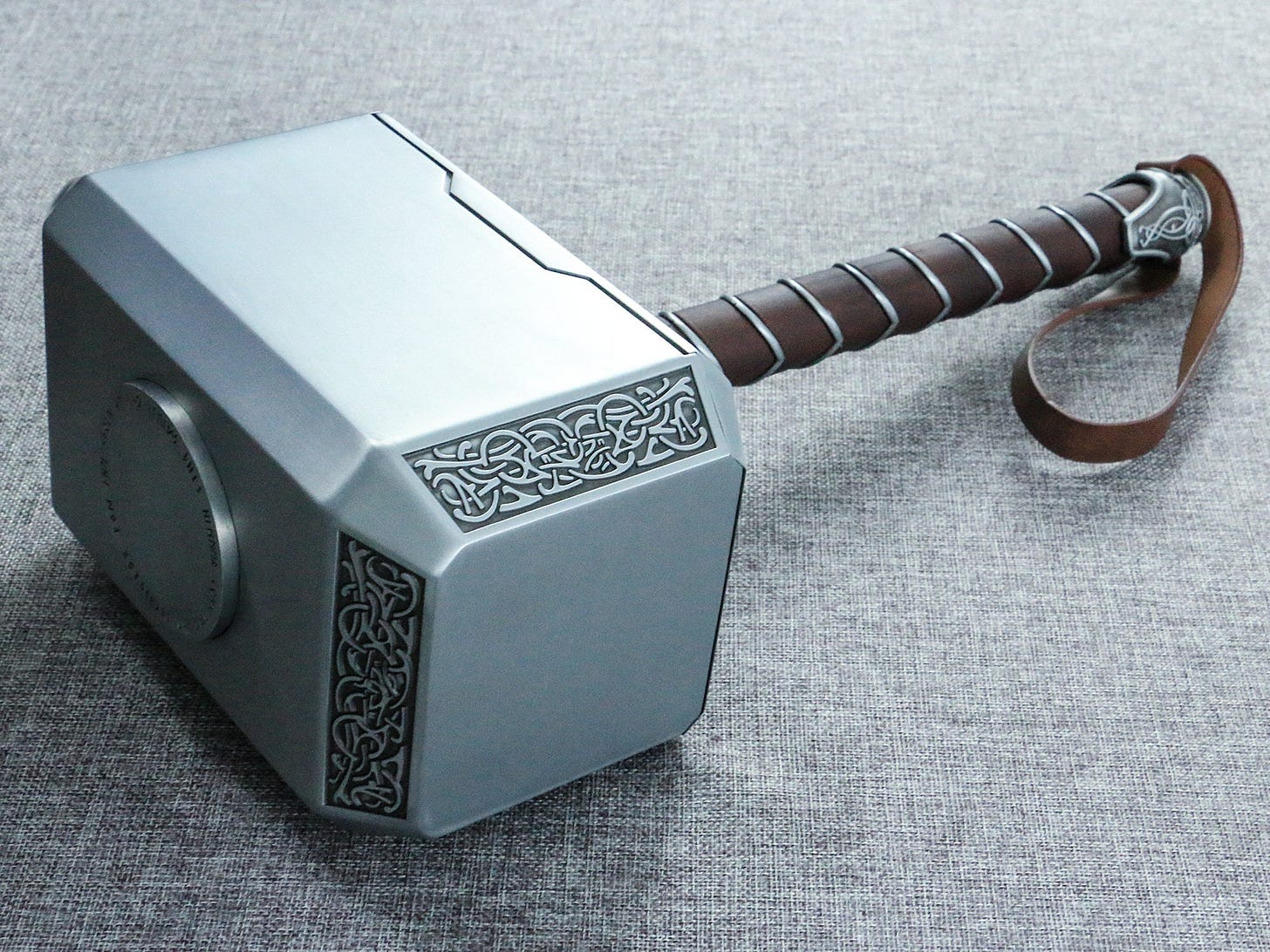

$435 hammers

Anyone remember the $435 government hammer? Way back in 1983 there was a massive hullaballoo about the Pentagon buying hammers for $435 each. In today’s money, that’s over $1400. People freaked out, President Reagan launched an investigation (the Packard Commission), and it was a whole big thing.

One obvious thought is that maybe these were some kind of Cadillac hammers, needed for extreme circumstances. I can easily imagine that you might need a hammer that will not fail no matter what stress you throw at it. Let’s say we want some hammers for the Apollo astronauts to harvest moon rocks, and they need to be used in a vacuum at 200 below zero without shattering. Astronauts can’t run to Home Depot for a replacement. To build the Cadillac hammer we’ll need materials scientists testing prototypes to destruction, and that sounds expensive.

Or perhaps we are investing in long-term, high-tech hammers. A few years ago my university replaced some sidewalk curbs with granite. This was controversial since granite curbs are much more expensive than poured concrete ones. The admin’s argument was that granite will last so much longer that this was a long-term investment and cheaper than getting new concrete curbs every few years.

Another idea is that the hammer supplier was ripping off the Pentagon, and it was just straightforward fraud. The government wasn’t wasting money so much as getting swindled. If someone takes your wallet you can’t really say that you wasted your money—criminals stole it.

It turns out that none of those explanations were correct. The true story was that the line-item listing the high-priced hammer was just an artifact of a complicated billing procedure:

[T]he equal allocation formula makes line item prices meaningless. Under this system the line item price does not reflect the item's true value. The equal allocation method calculates prices for large numbers of items in a contract by assigning “support” costs such as indirect labor and overhead equally to each item. Take a contract to provide spare parts for a set of radar tracking monitors. Suppose a monitor has 100 parts and support costs amount to a total of $100,000. Using the equal allocation method each part is assigned $1,000 in such costs, even though one item may be a sophisticated circuit card assembly, which requires the attention of high-salaried engineers and managers, and another item may be a plastic knob. Add $1,000 to the direct cost of the part and you get a billing price. This is what the government is billed, though not what the part is really worth—the circuit card being undervalued, the knob being overvalued. The need for billing prices arises because contractors want to be paid up front for items that are shipped earlier than others. (Source)

The lesson here is that when you drill down into something that looks like a waste of public funds, there can be something else going on entirely, like a benign bit of weird accounting.

Purchases we regret

Everyone has bought things they regret. Gadgets that looked cool but then broke right away, or a car that turned out to be a lemon, or an appliance that you used once and then just sat in a closet. Maybe you look back and think “that was a waste of money.” The government must surely do that on a grand scale. Like, “we shouldn’t have bought the war on terror for eight trillion dollars.”

The problem here is that it is only after the fact, in our post hoc judgment, that we can decide that it was money ill-spent. In advance those things all looked like wise purchases to somebody.

I have a friend who works for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. At the time of the Iraq War, I asked him if ODNI (or the other intelligence services) ever felt pressured by the administration to deliver intel that they wanted to hear. In other words, was anyone putting their thumb on the scale? He told me no— that there was a strong professional ethos at ODNI and CIA of getting the best information they could and giving higher ups the most accurate and fairest analyses possible. What the politicians did with them was a different story.

Suppose that CIA and ODNI tell the Bush administration that there is a 30% chance of Iraq developing weapons of mass destruction. (I am making this number up and have no inside information). It’s a political judgment as to whether that number is high enough to do something about it, or whether it is too low to bother. It’s not a slam-dunk decision either way. There’s a 70% chance of nothing going on, but also if a rogue nation gets WMDs, that’s pretty bad. What to do?

Bush decides to go to war. Then we find out that Iraq did not have any WMDs or a realistic path to get any. The intelligence services all say, “hey, we told you this was probably going to happen,” and in retrospect we judge that we wasted blood and treasure.

The problem is that in our ante rem judgment the Iraq War was arguably justified. To be clear, I am not saying it was justified, and I personally opposed it at the time. But it is understandable why others might have disagreed and supported the war prior to its start. In advance we can’t definitively say, “well, this will be a waste of money.” If we could, then no one would spend it. No, it’s more a case of “it seemed like a good idea at the time.” We are all fallible; hindsight is 20-20 and prediction is hard, especially about the future.

As with how much slack we should have in government, or which services we should purchase, political judgment is debatable. The truth is that people just complain that anything they don’t like is waste. Left, right, center, it doesn’t matter. That doesn’t mean that there’s some objective concept of waste that we can identify a priori. A keyword search won’t do it. How to best spend the public coffers is a matter of argument and honest toil, not a simplistic tale of waste.

Please note: not real programs. I made these up. They are fiction; do not write your Congresshuman.

Great article! The basic points are very good and true.

I've done many years work with the Australian Government (as a supplier of IT systems). Your system and ours are similar enough that I feel I can comment.

Corruption in the Australian (and I suspect US) civil service is rare and I never observed it myself. The civil servants I dealt with were usually well motivated and competent people. But I did observe an amount of waste (not slack) in Government.

A lot of the waste (not slack) is procedural and governance based. Governance processes are supposed to reduce waste and fraud, but they have unintended consequences. The demand to negotiate the lowest price on goods means that we often accept the lowest bidder, but the lowest bidder often turns out to be the bidder most adept at fudging project scope The net result is big cost overruns and contract variations. The insistence on fixed price contracts, which seems like a good way to constrain cost, means that a big risk premium is built into costings, and for reasons mentioned above, contract variations still occur anyway.

Another source of waste is just inertia. Department structures and procurement decisions end up being the fossilized history of the enthusiasms of previous governments. Sheer inertia plus external stakeholder self interest means that these programs and structures and decisions persist even though they are irrelevant to the current priorities and the money could be better spent elsewhere.

A quickie slash and burn exercise like DOGE was never going to solve these problems, because they are systemic. They are fixable, but only through diligence and cooperation between the political and bureaucratic players. Good government is a team sport and the 'government should be like a business' demand is moronic.

This is a great article, thank you! It addresses my two current pet peeves - "the government should be run like a business" and the short-sightedness of "just in time" (no slack) marketing, which seems to have spilled over into "just in time" for pretty much everything. Off topic, but on topic: sociopaths are unable to envision or plan for the future in ways that non-sociopaths do; they largely live in the moment. This mindset can result in terrible outcomes, when what they want in that moment is all they see, without any regard for the future. "I want it and I want it now" says His Majesty the Baby.