Making Things By Hand

Meditative flow

Binding books by hand has not changed a great deal since the Middle Ages. About the only real difference is that now tools can be heated by electricity and we have better glue. You might think that in these days of Kindles, iPads and mass-market paperbacks that hand bookbinding is about the most arcane, obsolete activity you can think of. Yep, that sounds about right. So naturally that’s what I want to talk about here.

There’s two kinds of bookbinders. The first kind are people who are crafters and do-it-yourselfers at heart and want to make scrapbooks, or a cool-looking grimoire, or put a binding on some fan fiction. To them I say, with full gladness of heart, vaya con dios. The second kind are people who are trained in the traditional craft methods of binding, and make books in period styles, or restore antiquarian bindings. I’m the second.

First off, there are astonishing binders and restorers out there, masters whose glue brushes I am not fit to wash. I would put my own skills at the level of an average professional.

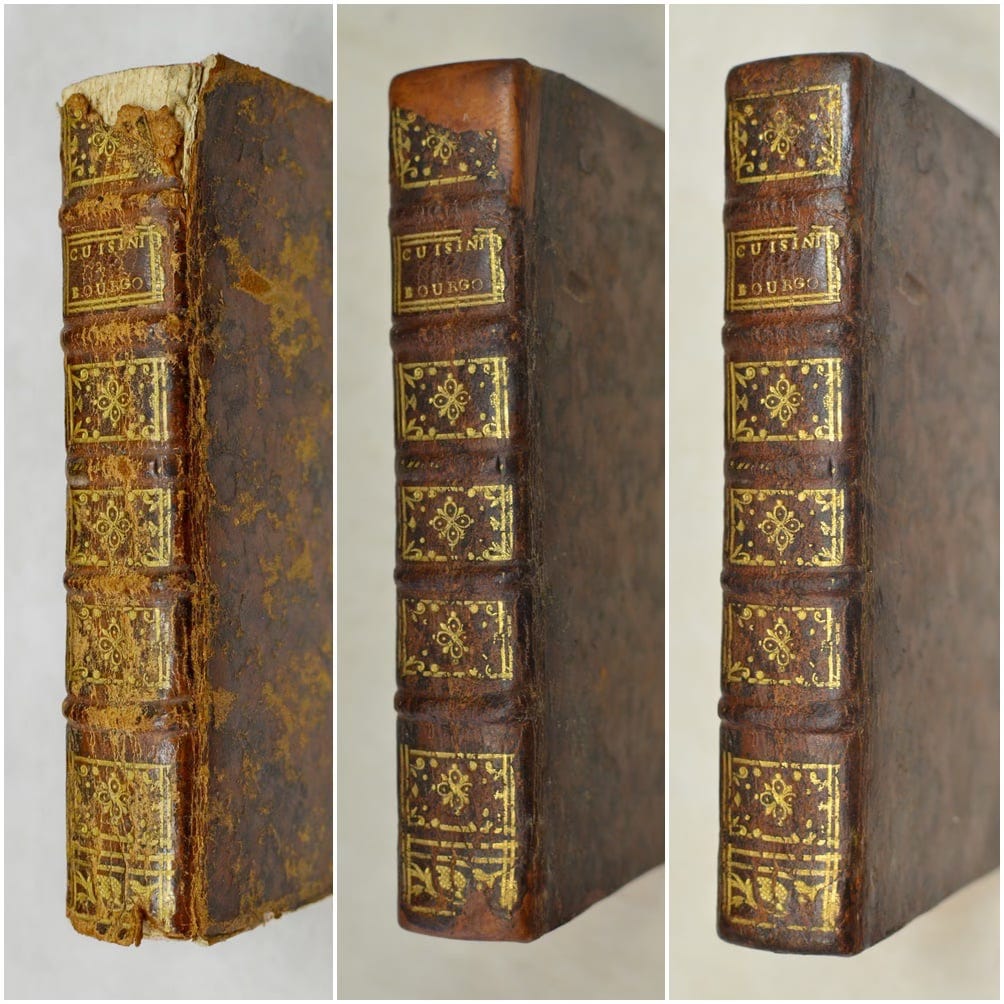

It is interesting the fine details that impress the experts tend to be lost on casual observers. Another binder once commended me on my letter spacing, a comment that in fact I treasure. Drilling down to that level of specificity assumes all the main features are satisfactorily done. Take a look at this before, during, and after restoration work by the French master Julien Jacques.

To a binder, this is mind-blowing. Frail, flaking, friable four hundred-year-old leather is insanely hard to work with. If Julien were a plastic surgeon, he would be in Beverly Hills doing boob jobs for billionaires. To non-binders, I’m guessing it looks like good work but less than supernatural. That level of craftsmanship is world-class difficult, but meta-easy.

Meta-hard and meta-easy

In The Omelette Fallacy I argued that there are tasks that

Look easy and are actually easy. (Example: brewing coffee)

Look easy but are actually hard. (Example: whistling with your fingers)

Look hard but are actually easy. (Example: making a good omelette)

Look hard and are actually hard. (Example: learning a new language)

Orthogonal to those distinctions is tasks that are meta-hard or meta-easy. With a meta-hard task, you can’t easily tell if you did it right. So proving Fermat’s Last Theorem looks hard, is actually hard, and is meta-hard because checking any proposed proof is difficult. Some hard tasks are meta-easy, like assembling a 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle or running a marathon. They are hard to do, but you can easily tell if you did them successfully. My claim there was that the Dunning-Kruger effect kicks in specifically for things that (1) look easy, (2) are actually hard, and (3) are meta-hard.

You can’t help but recalibrate your own self-assessment of skill when a task is meta-easy. The first time I went out on a really long bicycle ride, I thought I was in shape. I’d been playing a lot of tennis, and had done a couple of nice flat 23-mile rides along the river. So I was certainly ready for a 95-mile ride with two mountain crossings, right? Hahaha. No. Oh, I finished the ride all right, but I was at maximum bonk and I felt like a steamroller had gone over me at least twice. The buddy I did the ride with wanted to know if I was up for an additional 5 miles, just so we had a true century under our belts. Absolutely not. I couldn’t ride another five feet.

I most definitely reassessed my cycling fitness after that trip. The calibration was simple, because establishing cycling ability is meta-easy: just take a big ride and see how you hold up. After that 95-miler I decided that I needed a real training regimen before I tried anything like that again.

One of the frustrating things about intellectual work is that it is both hard and meta-hard. Does it look easy? I’m not sure; I’ve been immersed in it too long to have objective take. My suspicion is to outsiders some topics look hard and others don’t, even though in fact all real areas of inquiry are hard, and leveling up one’s knowledge is a major lift.

Working on things that are hard and meta-hard means you bang your skull against a granite block of a problem for a long time, and even when you finally come up with an answer you’re never sure that it is definitely right. The whole issue is too complex and subtle with a thousand interlocking factors. Whether you’ve cracked the problem or just your head is hard to tell.

It’s satisfying to complete a hard task. But it is simultaneously frustrating when that task is meta-hard and you’re never completely sure if you did it right. Maybe “frustrating” isn’t the right word. It’s psychically incomplete, I suppose.

argues that when confronted with hard questions we tend to substitute an easy question instead. “Am I good at my job?” is difficult to answer, but “am I working hard?” is easy to answer, so we tend to substitute the latter for the former. “Was that journal article I wrote an accurate and fruitful way to approach topic X?” Who knows. But I can go look at my citation count instead; that’s easy to do.One of the deeply pleasurable features of fine bookbinding, and handcrafts more generally, is that they are hard to do, but meta-easy. Did that end sheet paste down smoothly? Is the gold tooling crisp and clean? Is the book easy to open or is it too inflexible? There’s just loads of small questions like that which are completely evident upon inspection. I might second-guess a decision I made along the way, the but the results of that decision are easy to see.

That kind of immediate feedback is (1) immensely gratifying when things turn out well and (2) tells me what to do next time if it could be better. Maybe the leather corners on the covers are too bulky. Solution: pare the leather thinner next time. Maybe a bit of decorative gold tooling is off center a little. Solution: think about how to get better sight lines before the next time I use that tool. So few life decisions allow such prompt and actionable feedback. Certainly not my day job of being a professor, which is far from meta-easy.

Here’s the other pleasure of working with one’s hands: meditative flow. There’s an intrinsic logic to bookbinding. You can’t take things out of sequence, or nothing fits right. The book must be sewn, with the spine rounded and backed before the covers are cut, for example. Furthermore, the whole thing is a slow, deliberate, step-by-step process. Take sewing, for instance. I’m sewing up a 1551 copy of Boethius right now (well, not right, right now, but I was earlier today).1 The method for sewing antiquarian books cannot be done by a machine, and there is basically only one speed to do it. I’m doing exactly what the first binder did to sew that book 474 years ago.

So much of our lives is afloat in a sea of algorithms and advertisers and pundits, unsure of our next step, unsure if we took the right step. The satisfaction with traditional craftsmanship comes from the fact that our only real choices are personal and artistic, because the method is already there. The zone is pre-established, and just waiting for entry. What’s more, however hard the craft might be, at least it is meta-easy. That, I think, is a comfort.

Using an all-along kettle stitch on three sewing supports tied to a sewing frame, if you’re really interested.

I'm not a bookbinder, but I am an academic who likes working with his hands--and I'm sure I would love bookbinding. Actually, I'm currently on a sort of self-funded, indefinite sabbatical (trying my hands at homesteading) due in part to the issues you noted regarding the average college student in the post I just saw in Persuasion and in part to the issues you note here about how handcraft is meta-easy and being a professor meta-hard. As I was reading this post I was starting to think we should be friends when I saw the reference to Boethius, and then I knew I had to make a comment, for I named my first son, Severin, after Boethius.

Beautiful work.